Cable Slouches Toward Open Access

Cable operators have decided they need to back open access, but technical and regulatory hurdles stand in the way of sharing their lines

The broadband cable business has become a study in role reversals. The U.S. Federal Communications Commission, which might be expected to push for open-access rules, has never seemed too interested in such heavy-handed regulation of the Internet. And many cable providers--precisely those, one might think, that would surely resist open access with every fiber of their beings--are on record as supporting it. Some are even trying to implement it themselves.

Colorful times, indeed--but then, the open-access debate is no stranger to those. The flap began in earnest back in 1999, when AT&T Corp. cemented its position as the nation's biggest cable provider--having previously bought TCI, the country's number two multisystem cable operator (MSO)--by acquiring MediaOne. At the time, several Internet service providers (ISPs) realized that they needed a broadband pipeline into cable subscribers' homes and that AT&T, owing to its monopoly position in many major markets, could deprive them of just that.

Subsequently, AT&T refused to assure America Online, GTE (since merged into Verizon), and a few other ISPs that it would carry their services to its broadband subscribers. So the service providers took their case to local governments, some of which passed open-access rules forcing any cable provider to carry all ISPs on equal terms. Most local cable systems are monopolies (or at best duopolies), and as such they arguably ought to open their services to all--just like the companies that own electric power lines or natural gas pipes. That, at least, was what the local governments thought.

Since then, several of these local statutes have been invalidated by federal appellate courts, which have held that only two bodies have the authority to mandate open access, namely, the U.S. Federal Communications Commission (FCC) and Congress itself. And neither seems eager to take on such a withering regulatory task, especially with George W. Bush in the White House and his appointee Michael K. Powell, an opponent of open-access regulations, running the FCC.

Still, the open access issue is far from dead. Since 1971, telephone companies have been under a strict open-access requirement on all forms of data services using their lines, and these have come to include digital subscriber line (DSL) service, the main rival to cable for broadband subscribers. If cable providers fail to follow suit, diminished competition might make for poorer, and costlier, Internet service over cable, leading subscribers to choose DSL as their broadband medium. Already, Excite@Home, the ISP in Redwood City, Calif., that has exclusive arrangements with many cable systems, has had numerous service outages, winning no friends among subscribers, who cannot switch to any competing ISP.

In fact, the open-access model makes better business sense, according to some industry analysts. By signing on several paying ISPs, a cable system receives guaranteed revenue streams that will help pay back the cost of system upgrades, said Jeffrey K. MacKie-Mason, a professor of economics and public policy at the University of Michigan in Ann Arbor and a consultant favoring open access. With a single Internet service provider, there is a much greater likelihood that poor service will cause subscribers to defect to DSL.

Ultimately, the case for open access is simply this: Suppose a bunch of service companies provide their service through pipes controlled by a de facto monopolist. If the pipe owner decides to provide downstream service itself, then it may have a strong incentive to favor its own service provider at the expense of others.

The answer, it would seem, is open access. Recognizing that it may well be the best way to provide competitive services in the long run, cable companies are realizing that, at the least, they need to conduct tests to see if it can be made to work. But, as in so many of these access debates, the devil is in the details: when a cable company promises to open its pipes to all ISPs on equal terms, it faces a bevy of technical issues. What does "equal terms" mean? How can a fixed capacity for information transfer be divided up among possibly dozens of players in a way that will permit ISPs to provide customers with multiple levels of service--and how can all that be accomplished without hobbling transmission speeds? And how should the industry handle the cable provider's incentive to favor one ISP over another in technical ways that can never be written into an open-access agreement? Questions like these may explain why some of the open-access experiments to date have taken years to get off the ground, and have yielded only mixed results.

The details that house the devil

Regardless of what form it takes, open access will be fraught with all sorts of daunting technical challenges--many of which boil down to this one: how is a cable company supposed to divide up a fixed amount of information-carrying capacity among many ISPs? Such questions often force one to decide how to balance fairness against efficiency and, of course, how to guarantee that the cable provider cannot play favorites. Last September the FCC announced that it would hold hearings on the open-access question. Comments were due in January, and the hearings may yet provide insight into the thornier technological problems.

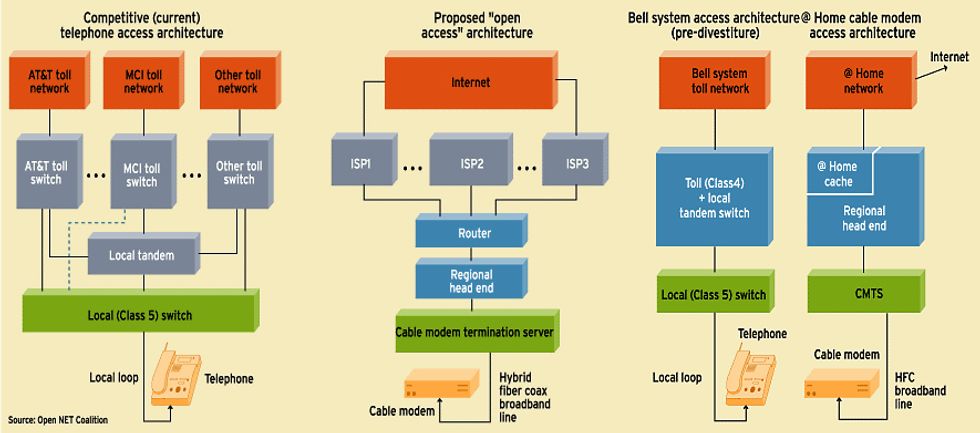

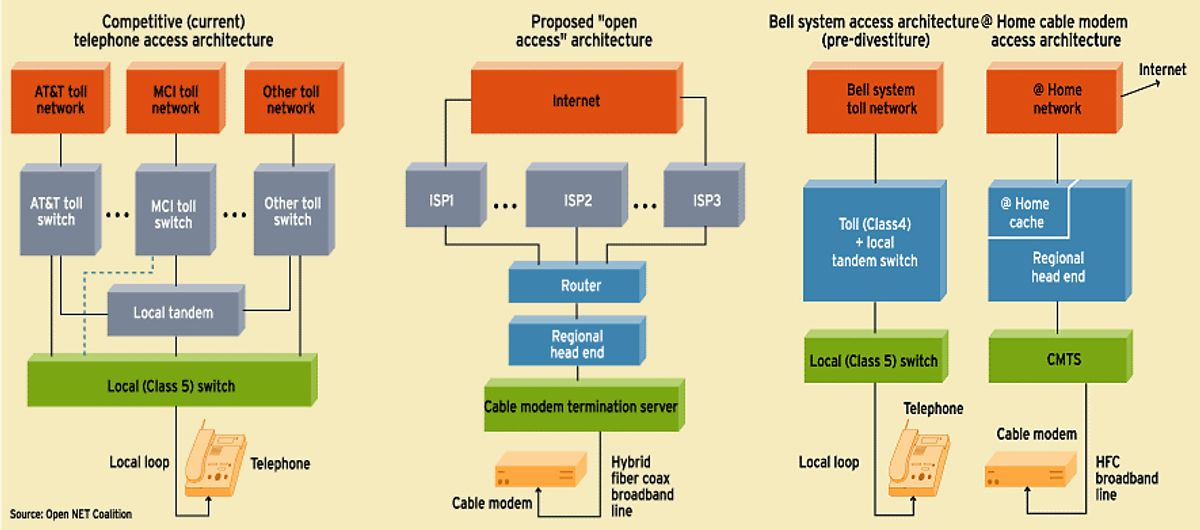

The first problem stems from basic network architecture. Phone-line connections are constructed in a hub-and-spoke configuration, designed from the outset for point-to-point communication. Since such connections already send out dedicated signals to each subscriber's home, it is a fairly easy matter to route them to the appropriate ISPs once they reach the phone company's home office. (That goes for DSL calls as well as ordinary narrowband connections.) By contrast, cable networks are arranged in a tree-like configuration, hearkening back to the industry's early days, when this setup was seen as the most efficient way to send television signals one way into homes. Because this structure mixes all upstream signals together on the same "trunk" of the tree, it complicates the task of assigning different ISPs to individual subscribers.

There may also be some prioritization difficulties. When a cable company offers only one ISP, it makes tradeoffs among many uses. Time-sensitive applications, like video streaming, can take precedence over, say, e-mail. Such tradeoffs will become all the more important in the future, with the growth of very time-sensitive applications like video-on-demand and teleconferencing. With multiple ISPs, how do you decide which gets priority? How do you allow different ISPs on your system to offer different access speeds?

The first solution is the crudest: frequency division multiplexing. Here, the cable company takes the bandwidth it has allocated to broadband and simply slices it up, giving one frequency range to each ISP, in much the way it does to TV stations. Frequency division has the advantage that ISPs know what they are getting. There is little chance that one of them will be favored over another, because spectrum is allocated in nice, measurable chunks. The downside, say its critics, is that it doesn't scale well. Each time a new ISP is added, the spectrum has to be sliced up anew.

Another problem with frequency division is that it wastes spectrum. Currently, cable-modem users receive any unused bandwidth available on the network during that millisecond when a page or application they have requested downloads to their PCs. If frequency division is used, though, the bandwidth that users could exploit is restricted to the amount allocated to their particular ISPs, while bandwidth reserved for other ISPs may go to waste.

Policy-based routing

Solutions that let all service providers share available spectrum are in principle more efficient, but raise some tricky problems of their own. They generally use time-division multiplexing to allocate capacity, co-mingling packets from competing ISPs. They also require the use of intelligent switches to maintain network performance.

One such solution is so-called policy-based routing. With this approach, network managers configure routers so that they direct traffic based on predefined rules, the so-called policies. Certain packets of information could be tagged so that they receive preferential treatment, for instance. Again, examples might be voice communications or streaming video that must be processed in something approaching real time. Cable networks might also allocate capacity among ISPs based upon the speeds each one promises customers. Subscribe to a premium ISP, and the network's policy-based routers will always give priority to your packets. Pay less each month and you have to put up with slower downloads.

Critics of policy-based routing charge that it, too, fails to scale very well. Add more ISPs, and more policies must be created, increasing the network's complexity. If everyone is downloading the latest streaming Web concert, the network must decide which users get their information first, as well as which ISPs receive preference.

Others charge that policy-based routing would let system operators discriminate in favor of their own ISPs. "The network owner has the ability to filter or control the flow of information," charges a Consumer Federation white paper [see "The Great Open-Access Argument"]. "It can give priority to its affiliate's data and ensure higher quality than the data of independent ISPs."

Another solution, perhaps the most promising, involves virtual private networks (VPNs), as they are called. With these, packets from an ISP are encrypted and sent (tunneled is the technical term) direct to that ISP's server, where they are in turn routed to the Internet backbone. Because of the encryption, the server of each ISP can read only those packets that belong to that ISP's customers. Thus, the system runs like a collection of virtual networks. Each ISP gets to decide for itself how to assign priority among the data packets sent by its users. Overall, the cable system must then use some sort of policy-based routing to divide up capacity among the ISPs.

Like policy-based routing, VPNs allow cable systems to offer differing service levels to different ISPs. VPNs are also said to be the most scalable of the network management solutions, because they require no alteration to the overall network structure. However, because the information must essentially be packetized twice, there's a bandwidth penalty.

Putting open access to the test

The technical problems of open access may help explain why it has never really been served up to a mass market--not even in Canada, where open access is mandated by law.

In an early test, GTE let Clearwater, Fla., users choose from America Online, CompuServe, and GTE.net. But the tests, though successful, were halted when the local cable system being used was put up for sale.

In Canada successful trials took place last fall and winter over VideoTron's cable system in Montreal. But these trials came roughly two and a half years after Canada passed a law requiring cable companies to open their systems to many ISPs. "The only way we could achieve open access in Canada was through a law," said Jay Thomson, president of the Canadian Association of Internet Providers. The Montreal trials employed virtual private networks, and rollout to general subscribers has been scheduled for later this year.

AOL Time Warner Inc., of New York, is also testing open access, in Columbus, Ohio, a project that began as part of Time Warner's efforts to win approval for its US $106 billion merger with AOL. According to documents filed with the FCC last August, that system will use policy routers to direct packets from individual ISPs to their respective customers. Servers owned by individual providers will probably not be located at the head end--that is, the cable system's general distribution point. Instead, ISPs will be required to manage traffic once it leaves the head end. AOL may allow service providers to share caching servers. Others involved in the preliminary tests were CompuServe (an AOL subsidiary) and Road Runner, the incumbent ISP, located in Herndon, Va. Three more ISPs, New York City's Juno, Microsoft's MSN, and RMI.net, may join the tests in late 2001, according to a news report in ISP-Planet.com, an on-line Internet.com publication.

AOL Time Warner claims subscribers will be able to choose a service provider and speed they desire. The trial will test whether customers will be able to switch from one provider to another seamlessly, without the aid of a technician. As for scalability, the FCC documents say, "We believe that capacity planning will depend primarily on the number of customers and bandwidth usage patterns, and not on the number of ISPs carried on the cable system."

Meanwhile, AT&T is conducting its own open-access trials in Boulder, Colo. The tests, which may involve as many as eight ISPs, will be limited to 500 subscribers. While the company has not gone public with details about the system architecture, it has outlined plans for how it proposes to work with competing ISPs. These must demonstrate that their services are compatible with the AT&T cable network, and they will pay a monthly fee for access. Broadband subscribers will be able to call up an application on their PCs that lets them choose an ISP in much the way new computer owners can select a dial-up ISP from a menu on their desktop PCs.

The Boulder trials will be followed by additional testing in Massachusetts in the fall of this year. The idea, apparently, is to make ready for 2002, when Excite@Home's contractual monopoly on AT&T's cables ends and AT&T starts extending access to other ISPs. (Excite@Home will continue as AT&T's default provider until 2008.) "Excite@Home said it would work with AT&T to provide connectivity services to third-party ISPs to deliver broadband services," AT&T announced in a prepared statement last year.

Once system penetration by Internet users reaches 10--15%, today's cable systems will have trouble keeping up

AT&T's plans became somewhat ambiguous after it announced its intention to turn its broadband division into an entirely separate company. Compounding this ambiguity, many AT&T shareholders say they will oppose the break-up.

Nonetheless, since none of this has happened yet, AT&T continues to call the shots for its broadband division. And just as the future of AT&T Broadband remains unclear, so does the future of the open-access debate. Even as open-access field trials get under way, any significant deployment still seems a year or more in the future.

AOL Time Warner leads the way

Given the technical problems and the cable industry's slowness in reacting to them, analysts like MacKie-Mason and others believe it could take several years before cable systems supporting multiple ISPs become commonplace. So far, tests have been confined to just a few hundred homes, sometimes those of the cable systems' own employees. Scaling up to an open-access cable network serving 100 000 or more subscribers has yet to occur, but would probably compound any challenges encountered during the initial tests.

Those challenges may resemble obstacles that have long stymied interactive TV--namely, the difficulties of managing a network fast enough and robust enough to deliver high-bandwidth applications seamlessly to large numbers of users on request. Ironically, a cable system that does a good job of balancing the demands of competing ISPs on its system risks attracting more users who will eventually overburden it. "Once system penetration by Internet users reaches 1015 percent, today's [cable] systems have trouble keeping up," say researchers at cable equipment maker Broadband Access Systems Inc., Minnetonka, Minn., in a white paper.

That's the pessimistic view. Come what may, open access trials will surely continue--albeit cautiously. As larger-scale rollouts occur, subscribers will likely be offered limited options at the start. Then gradually more ISPs, each providing varying levels of service, will be added. Look to AOL Time Warner to lead the way. An antitrust settlement with the government forbids the company from offering its own Internet service, AOL, until a competitor is up and running.

William Sweet, Editor

About the Authors

MARK INGEBRETSEN and MATT SIEGEL are both free-lance writers. Ingebretsen, based in Iowa, writes a regular column for TheStreet.com. Siegel writes and edits articles about business, and has done consumer-advocacy work on competition policy. He has worked for Fortune, American Lawyer, and Physics Today.

To Probe Further

The U.S. Federal Communications Commission tracks the progress of prospective hearings on open access and publishes comments at https://www.fcc.gov/broadband. The OpenNETCoalition (https://www.opennetcoalition.com) has working papers and news items in support of open access.

A General Accounting Office report detailing the economic, technical, and legal issues governing broadband deployment is at https://www.gao.gov/new.items/d0193.pdf The Center for Democracy & Technology has also published a detailed paper favoring open access, at https://www.cdt.org/digi_infra/broadband/backgrounder.shtml. The CableLabs Web site at https://www.cablelabs.com has news on efforts to create uniform network management standards for different systems.