In much of the world, an American drone flying overhead means danger: Predator drones and the like can unleash fury out of the deep blue sky. But drones can also help war-torn countries recover, argued Ryan Baker, CEO of drone maker Arch Aerial, at a SXSW Interactive talk yesterday. His company hopes to use its drones to identify locations that are likely to be riddled with unexploded bombs from past wars.

Baker wants to start with Laos, which bears the terrible distinction of being the most heavily bombed nation ever: During the height of the Vietnam War, the country was pounded with about 2 million tons of ordnance. And Laotians today are still suffering the effects of that bombardment, as unexploded shells and landmines still litter the landscape. The biggest threat comes from the cluster bombs dropped during the Vietnam War, which scattered small explosives about the size of tennis balls.

In Laos, “there have been some 12,000 accidents related to UXO [unexploded ordnance] since 1973,” said Baker. Most deaths and injuries occur when people try to remove unexploded bombs, he said, or when local farmers till their fields.

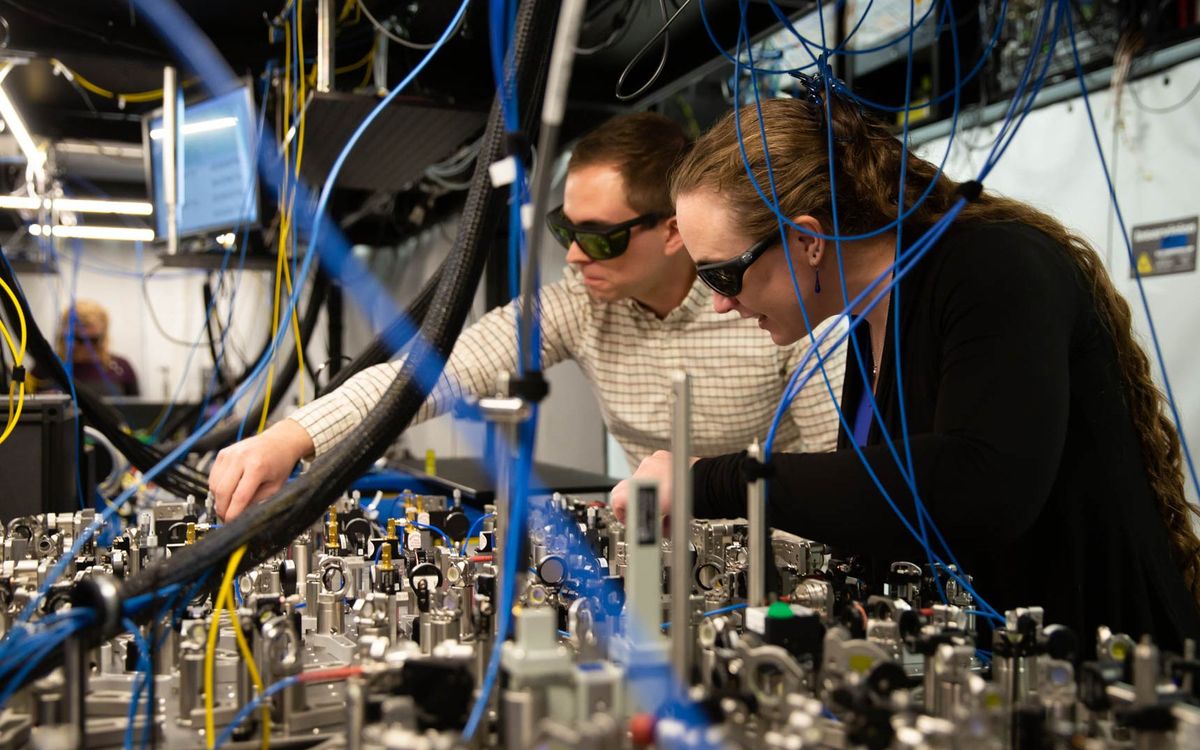

Baker said his company’s octocopter will carry a laser imaging system known as LIDAR (often used in self-driving cars) to survey terrain and identify locations where unexploded ordance will likely be found. LIDAR is useful because it can see through vegetation and create precision maps of the ground. By flying drones above Laos’s forests and fields, surveyors can look for topographical features signifying places that might have been targeted by bombing campaigns—such as bunkers and trenches, Baker explained. Arch Aerial plans to do some test runs this year in cooperation with one of the humanitarian groups working on unexploded ordance in Laos.

This initiative is only possible because of rapid advances in LIDAR technology, Baker said. “A few years ago, a LIDAR system was the size of this table,” he said, “and had to be fitted into a gutted airplane.” And conducting a survey by plane requires plenty of money and compliance with flight regulations. Now, with a small and cheap LIDAR system aboard a drone, a surveyor could create an aerial map with “risk profiles” of the landscape before setting foot on the ground.

Surveyors will still have to deal with public perception and the stigma surrounding drones, Baker noted, since Americans operating strange equipment are sometimes viewed with suspicion. But there’s an easy way to solve that problem, he said: Just hand the controls to a local.

Eliza Strickland is a senior editor at IEEE Spectrum, where she covers AI, biomedical engineering, and other topics. She holds a master’s degree in journalism from Columbia University.