PHOTO CREDIT: SOLAR IMPULSE

This morning at 7 a.m. local time, the Solar Impulse plane lifted off from Payerne air force base in Dübendorf, Switzerland, for its groundbreaking 24-hour flight. The flight was supposed to take place last week, but problems with some communications electronics prevented lift off. But today everything is proceeding according to plan. According to spokesman Lucas Chambers, Solar Impulse chairman Bertrand Piccard started the day with an invocation for the assembled peanut gallery: "This airplane," he said, "is here to prove that renewable energies are not just pornography for tree huggers."

Meanwhile, Andre Borschberg, Solar Impulse CEO and daredevil, is tucked away in his tiny cockpit, from which he will pilot the monster with the 61-meter wingspan for the next 24 hours. But as you might imagine, this isn’t the kind of plane you set on auto-pilot and go have a coffee and a snack. Borschberg will need to be alert for the entire time because the plane must not tilt more than five degrees: If it does, its massive wingspan and light weight could cause the plane to spin out of control. So, Borschberg needs to remain alert enough to keep the plane straight for all 24 hours of his journey—even in complete darkness.

Here are six questions I thought you might have about the trip.

The plane is solar-powered, but it will fly all night. How does that work?

The plane’s approximately 12,000 photovoltaic cells soak in the sun’s rays from 7 a.m. until sunset about 15 hours later (sunset, according to the Solar Impulse site, is at 22:00). During that time, they simultaneously power the plane’s four 10-HP propeller engines and charge four polymer lithium batteries onboard, which don’t start being depleted until the sun sets. “The big question will be whether the pilot will be able to save sufficient energy as to fly right through the night,” Bertrand Piccard was quoted as saying in a press release.

But it’s looking good: According to a blog post on the Solar Impulse site, in its eighth test flight, “the HB-SIA operated entirely energy-positive for the first time. This means we came back with significant more energy than we took off with.” (The site does not allow linking to specific posts so if you’d like to find the exact post, go here and search by date for the entry marked 06-05-10.)

How will Borschberg stay awake all night?

I mentioned in my last Solar Impulse update that research has shown that just 24 hours of sleep deprivation mimics the effect of a 0.10 blood alcohol level, illegal in Canada, the United Kingdom and the United States.

But researchers have also found that 20 minute-catnaps, spaced out properly, can stall these effects. That’s because a full complement of sleep includes 90-minute cycles of four stages of sleep, each more deep than the previous one, and finally REM sleep, in which the sleeper dreams. The average person has four or five such 90-minute cycles per night. If you’ve ever been forcibly awakened 40 minutes into a night’s sleep you know how disoriented and groggy you feel. The magic bullet, research has shown, is the 20 minute nap—you’ve entered only the lightest stage of sleep, and on waking you feel completely alert.

How does ground control make sure the far-away pilot never stays asleep for more than 20 minutes? You might think staying awake for 24 hours is a piece of cake—we’ve all done the all-nighter—but these are extreme conditions. Borschberg will be in near-complete darkness, illuminated only by the soft light of the instrument panel. He’ll be strapped into place in a cockpit roughly the size of a sarcophagus. He won’t be able to stand up or even stretch to get his blood flowing.

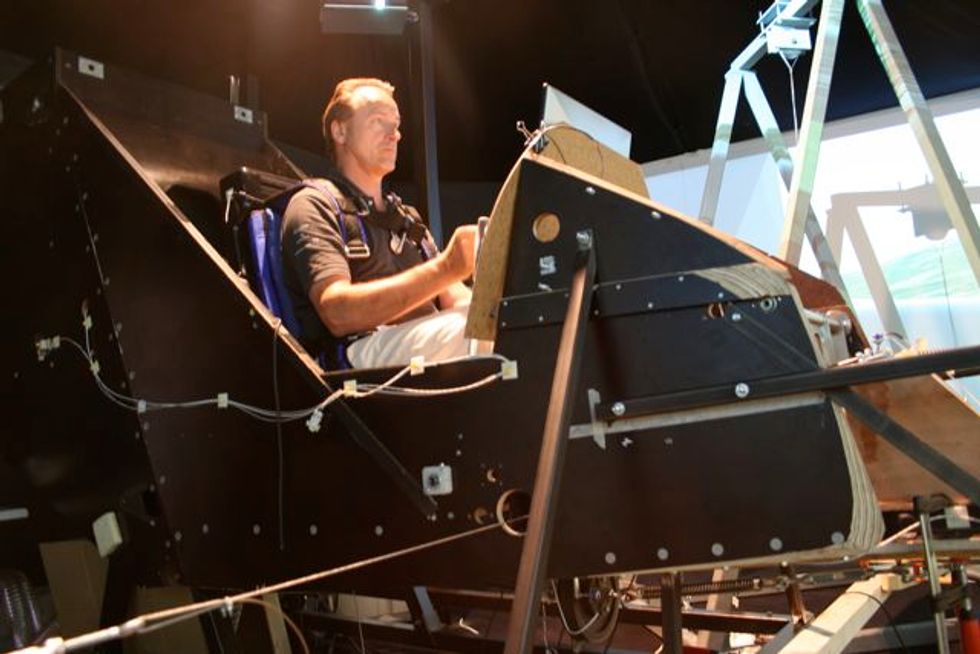

The answer was designed at Solar Impulse partner Ecole Polytechnique Federale de Lausanne (EPFL), the Swiss university that is also home to the Blue Brain project. In 2008, EPFL student Walter Karlen and his colleagues showed me a haptic vest they designed to monitor the Solar Impulse pilot’s state of consciousness. The vest is also designed to zap him awake with a haptic buzz whenever the monitors show that he has dipped out of consciousness.

My colleague Morgen Peck wrote about the vest for Spectrum last year. Here’s how it works.

A belt running around the ribcage measures respiration; gel electrodes fixed to the pectoral area read out an electrocardiogram; and other electrodes detect muscle activation. The whole thing runs off a battery that's also mounted right on the shirt.”

I don’t know if the vest design I saw at EPFL will be used on this flight, or whether it will be used in future flights. But the principles behind it have definitely been integrated into the pilot’s suits, according to this Sunday Times article:

[Bertrand] Piccard and Borschberg have already “flown” a 25-hour non-stop stretch in the simulator at Dübendorf. They managed to stay alert, helped by a vibrating system in their flight suits that wake the pilot if he sleeps more than a few minutes and lets a wing drop.

Oh, also, the engineering team purposefully made the unpadded seat in the cockpit really, really uncomfortable.

If the pilot can't move for 24 hours, how does he go to the bathroom?

He’ll take along a few of these and hope for the best.

I'm not kidding. When I asked the question at the Solar Impulse hangar, spokeswoman Rachel Bros de Puechredon pulled out this very package to enlighten me. It contains blue crystals that form into a gel when hit by a liquid.

And how will the pilot get any privacy, given the intrusive, always-on camera that will capture Borschberg's every blink for the duration of the flight? "There will be a webcam on the pilot, but with a minute’s lag so he a take a piss in private,” Solar Impulse’s Bertrand Piccard told the Sunday Times.

How will he survive for 24 hours at 8500 meters?

Because Borschberg won’t be flying above 8500 meters, there will be no need to pressurize the cabin, and oxygen won’t be necessary until he hits about 3600 meters. The cockpit temperatures will range between +35 to -20 degrees Celsius. Borschberg will be wearing a warmed, insulated flight suit and so will the batteries: Solar Impulse engineers designed special thermal insulation to conserve the batteries’ heat to keep them nice and toasty.

What if something goes wrong?

Borschberg has a parachute.

Why 24 hours?

They’ve been ramping up with short flights for a few months. In early April, the HB-S1A flew for 90 minutes, and a month and a half later a Solar Impulse pilot had it in the air for over 14 hours.

Today’s test flight will ensure that the batteries really can power the plane through a full day-night cycle. If the flight succeeds, then the engineers will simply scale up in increments of day-night flights. Next year the Solar Impulse team plans to do a transatlantic flight, and by 2013 they vow to circumnavigate the globe. I don’t know if they mean "without landing," because it might be tough to survive five days on those catnaps, and I imagine you’d run out of fresh portable urinals.

But the Solar Impulse plane that makes the hop across the pond won’t be the same one that does today’s 24-hour flight. They’re working on an upgraded model that might be able to accommodate two pilots.

For more answers to questions you didn't know you had, go the Solar Impulse Night Flight web site, where their press team will be live-blogging the event.

Sally Adee, formerly an associate editor at IEEE Spectrum, is now a technology features editor at New Scientist, in London. She says it was an honor to write her last feature for Spectrum about the European Space Agency’s Loredana Bessone, a woman she considers a role model. “One day, I’m going to hit her up at ESA to start training me as an astronaut,” she says with a wink. “Right after I get sick of playing roller derby in London.”