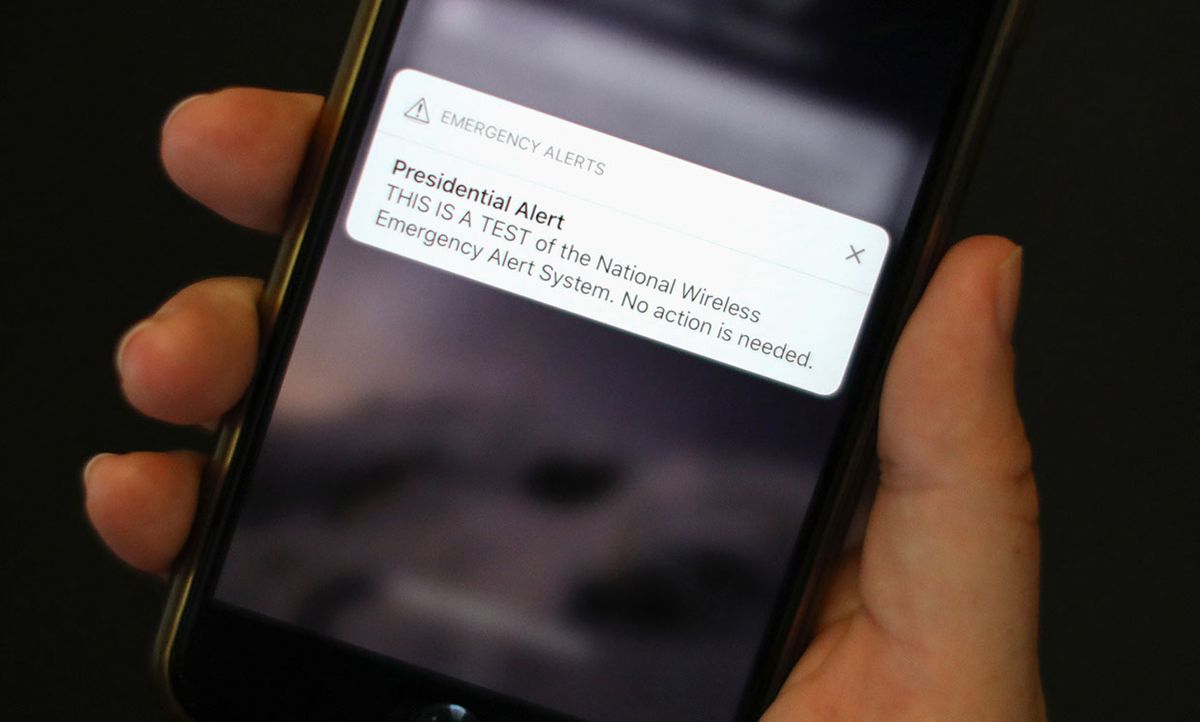

The U.S. Federal Emergency Management Agency (FEMA), in coordination with the Federal Communication Commission (FCC), on Wednesday conducted a nationwide test of the Presidential Alert feature of its Wireless Emergency Alert (WEA) system.

While there have been previous tests of the alert system, and wireless AMBER Alerts concerning missing children or dangerous weather conditions have been sent out for years, this is the first time that the alert system feature that permits the nationwide communication of a national emergency situation has been tested.

The WEA system, along with the more familiar broadcast Emergency Alert System (EAS) and the National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration (NOAA) National Weather Radio system, make up the federal core of what is known as the Integrated Public Alert & Warning System (IPAWS). Initial reports seem to indicate that the Presidential Alert test, along with the test of the Emergency Alert System that accompanied it, operated generally according to plan with some 75 percent of the 225 million cellphones in the United States likely receiving the alert.

There have been sporadic reports of people not receiving the Presidential Alert, many on AT&T wireless service, which according to FEMA can happen for a variety of reasons including not having good cell service or the phone being in use during the test. The alert message is supposed to be delayed and then pushed to your phone once you hang up, but some people said that never happened. Your carrier may also not be a participant in the Wireless Emergency Alert system, but it is supposed to let you know if it’s not. FEMA has asked that if you did not receive the alert, that you contact it at FEMA-National-Test@fema.dhs.gov with as much information about your situation at the time as possible.

Of course, not everyone who received the Presidential Alert was happy about it. While one can opt-out of other types of emergency wireless alerts, one can’t opt out of the Presidential Alert. Some people claimed that by not allowing them to opt out, the alert violates their constitutional rights, and unsuccessfully went to court to try to stop the test. Others were concerned that President Trump would co-opt it for his own political purposes, which the law forbids [PDF]. The same arguments about potential presidential misuse of the alert system were raised against President Obama on a previous alert test.

Politics aside, it has taken a lot of time, effort, and funding, as well as overcoming more than a few technical hiccups, to get to this point. The Integrated Public Alert & Warning System has its origins in President George W. Bush’s 2006 Executive Order 13407—Public Alert and Warning System. The executive order came in the wake of Hurricane Katrina in 2005 and its exposure of the weaknesses and failings of local, state, and federal emergency communications [PDF].

The objective was to create an integrated infrastructure with a unified interface for local, state, and federal agencies to communicate warnings to the public using the various emergency alert systems. As described in the executive order, FEMA was to create “an effective, reliable, integrated, flexible, and comprehensive system to alert and warn the American people.” Some US $25 million was set aside over three years for studies into public notification efforts and to define the new integrated alert system.

While the intentions were worthy, the implementation of the integrated alert system has not exactly been speedy. For instance, the Government Accountability Office (GAO) wrote [PDF] in 2009 in its second progress report into creating the integrated alert system that “the reliability of the national-level relay system—which would be critical if the President were to issue a national-level alert—remains questionable due to a lack of redundancy among key broadcasters, gaps in coverage, insufficient testing of the relay system, and inadequate training of personnel.” It also pointedly noted that nothing really had changed from its 2007 progress report.

With Congress expressing its frustration with FEMA’s slow progress, the new Obama administration did begin to advance the implementation of the integrated alert system. After two successful pilot tests in Alaska, a more comprehensive test was attempted in September 2011. The results of that first national test of the Emergency Alert System was less than spectacular, with software problems and weak signals originating with FEMA sent to the emergency system broadcasters among the problems cited.

Despite problems, FEMA rolled out [PDF] the Integrated Public Alert & Warning System beginning in April 2012. In light of the 2011 test, FEMA planned to do another test in 2012, but this didn’t happen until September 2016. Part of the reason was that, as the GAO once again reported in 2013, issues with system reliability, coverage, and training remained. Furthermore, to have true national coverage there had to be a sufficient number of cellphones sold in the United States possessing the capability to receive the emergency alert. It would be a few years yet before that point was reached.

In early 2016, Congress, still frustrated with the time it was taking to get the emergency alert system up and running, unanimously passed the Integrated Public Alert and Warning System Modernization Act of 2015 [PDF]. Among other directives, the act ordered FEMA to modernize the equipment being used, to improve training of those using the system and receiving alerts from the system, to increase the areas covered by the alerts, to allow alerts in languages other than English, as well as to conduct at least one test every three years.

Another alert test was conducted in September 2017, which focused on the Emergency Alert System and National Weather System aspects of the integrated system. This test went better, but there were still nagging issues with coverage and reliability. The erroneous Hawaii emergency missile test in January 2018 also highlighted a problem regarding who should be authorized to send out an alert, as well as the inability to quickly recall an incorrect alert.

Hawaii has addressed these weaknesses [PDF] by requiring two people to sign off when an alert is sent and the creation of an alert-cancellation template. The incident also caused other state and local emergency-alert officials to review their procedures and FEMA to increase its training of officials concerning the use of the system.

It will be interesting to see what the results of this latest test are, especially in geo-targeting. A major objective of the Wireless Emergency Alert system is to allow for the precise targeting of emergency messages to particular geographical areas. One doesn’t want alerts being sent to people that don’t need them. How to make this happen has been a point of in-depth technical discussion [PDF] regarding how to create specific coverage without overlapping or missing areas.

According to its official business case, at least $184 million has been spent by the federal government developing the Integrated Public Alert & Warning System since 2007 and another $71 million on its operations and maintenance. How much local and state agencies, as well as carriers, have spent supporting the system is unknown, but the amount is probably as much if not a lot more.

FEMA has not announced when it will hold its next test, but it is likely that it will happen next September during National Preparedness Month. While some may find the test annoying, from a management-of-risk perspective, it is beneficial to take a few minutes each year to discover weaknesses in the system before it is needed, not afterwards.

Robert N. Charette is a Contributing Editor to IEEE Spectrum and an acknowledged international authority on information technology and systems risk management. A self-described “risk ecologist,” he is interested in the intersections of business, political, technological, and societal risks. Charette is an award-winning author of multiple books and numerous articles on the subjects of risk management, project and program management, innovation, and entrepreneurship. A Life Senior Member of the IEEE, Charette was a recipient of the IEEE Computer Society’s Golden Core Award in 2008.