In collaborative research between Georgia Tech and the University of Toledo, both computer modeling and experiments have demonstrated that when pressure is applied to a superlattice structure the bonds that link the nanoparticles making up the structure behave as though they were gear-like, molecular-scale machines.

Superlattices form when an almost atomically thin layer of one material is laid down over another in an alternating pattern, creating numerous interfaces. IBM has used graphene-based superlattices to build experimental photodetectors.The researchers in this latest resarch believe that this type of superlattice could prove useful for developing molecular-scale switching, sensing and even energy absorption applications.

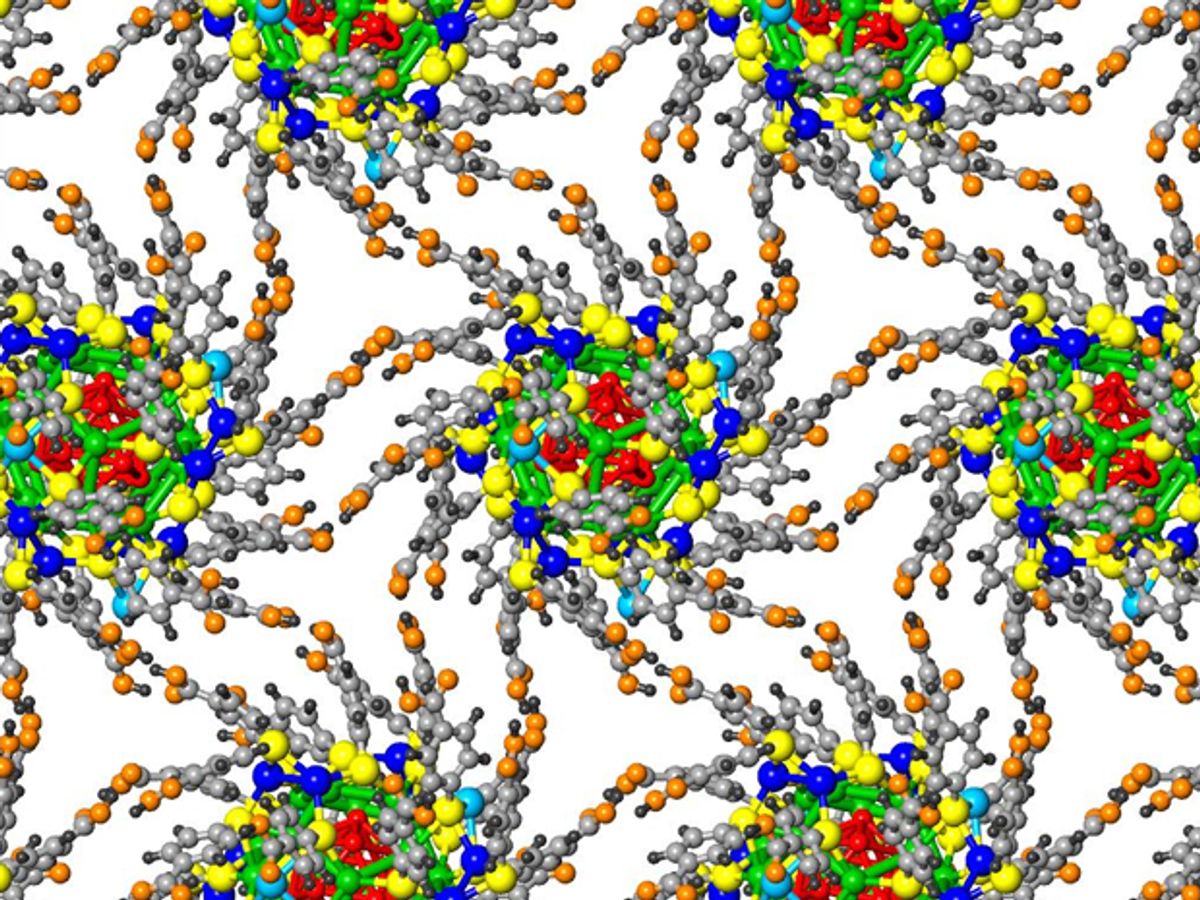

The appearance of gear-like movement in the structure is the result of the hydrogen bonds that connect organic molecules surrounding clusters of silver nanoparticles in the superlattice. Under pressure these bonds move like a hinge keeping the nanostructure from breaking.

While this hinge-like movement was unexpected, the pressure itself also had an unexpected consequence of softening the superlattice so that that subsequent compression of the structure could be done with less force. The researchers discovered that after the structure had been compressed by about six percent of its volume, the pressure required for additional compression suddenly dropped significantly. This drop occurred as the nanocrystal components rotated, layer-by-layer, in opposite directions.

“As we squeeze on this material, it gets softer and softer and suddenly experiences a dramatic change,” said Uzi Landman, a professor in the School of Physics at the Georgia Institute of Technology, in a press release. “When we look at the orientation of the microscopic structure of the crystal in the region of this transition, we see that something very unusual happens. The structures start to rotate with respect to one another, creating a molecular machine with some of the smallest moving elements ever observed.”

In the video below you can see the structure of the superlattice, which consists of clusters with cores of 44 silver atoms each. Thirty molecules of an organic material known as mercaptobenzoic acid (p-MBA) protect the silver clusters. The organic molecules are attached to the silver by sulfur atoms. Again, the parts that move, the “hinges”, are the hydrogen bonds that attach the organic molecules.

The research, which was published in the journal Nature Materials (“Hydrogen-bonded structure and mechanical chiral response of a silver nanoparticle superlattice”), described the production of the superlattice structure through self assembly. In a solution, clusters of the silver nanoparticles and organic molecules assemble themselves into the larger superlattice, guided by the hydrogen bonds, which can only form between the p-MBA molecules at certain angles.

As if producing some of the tiniest mechanical objects ever weren’t enough, the researchers believe there work also represents the largest solid ever mapped in detail using a combined X-ray and computational techniques.

Dexter Johnson is a contributing editor at IEEE Spectrum, with a focus on nanotechnology.