Researchers at the University of California at San Diego have developed a composite nanomaterial that can convert 90 percent of the sunlight it captures into heat, making it an ideal candidate for solar absorption at concentrating solar power (CSP) plants.

"We wanted to create a material that absorbs sunlight [and] doesn't let any of it escape. We want the black hole of sunlight," said Sungho Jin, a professor at UC San Diego, in a press release.

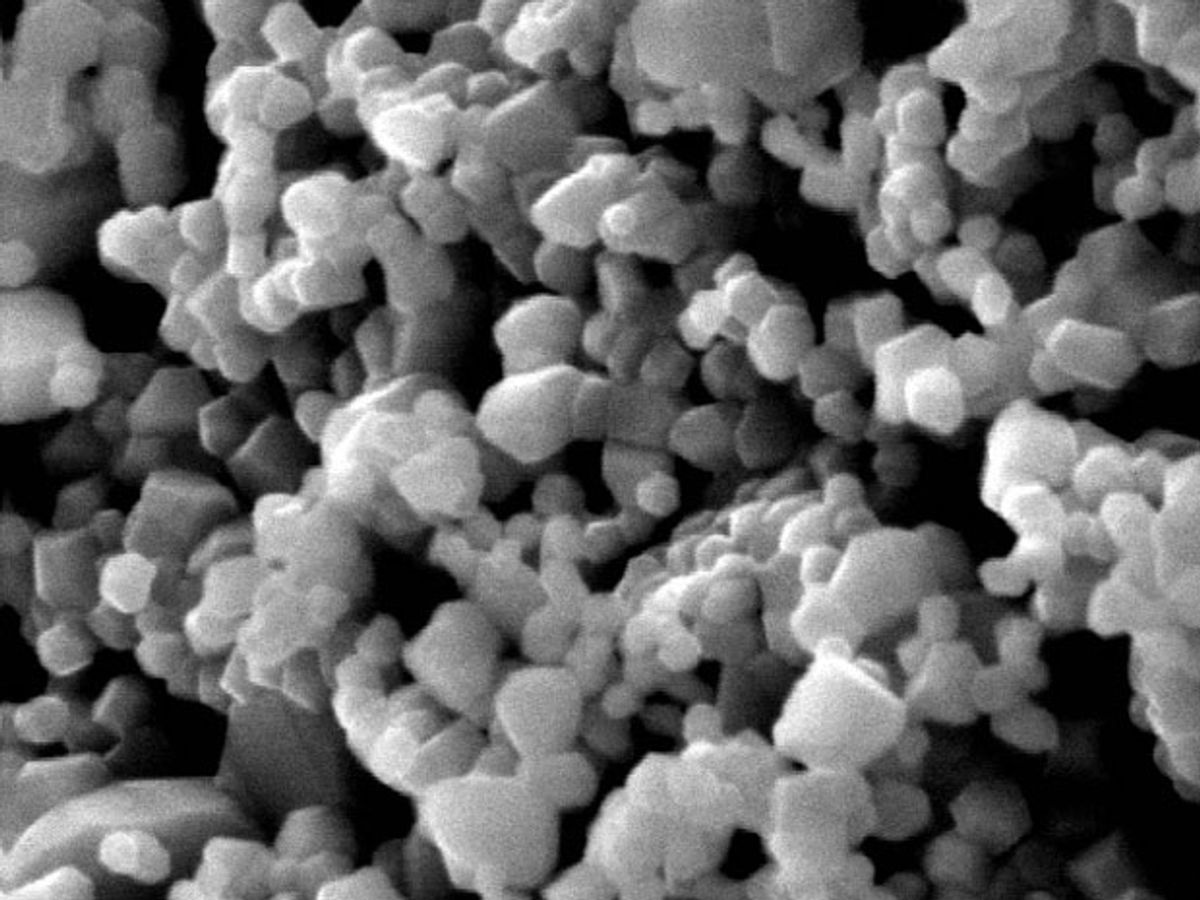

The hybrid material, which is described in the journal Nano Energy, combines copper oxide nanowires with cobalt oxide nanoparticles to create a multi-scale surface for the material with dimensions ranging from 10 nanometers to micrometers. This multi-scale surface gives the material its extraordinary efficiency at trapping and absorbing light.

Previous research has proposed the use of nanowires for concentrating the sun’s rays into a very small area of solar cells. And copper sulfide nanoparticles in combination with single-walled carbon nanotubes have proven effective in converting both light and thermal radiation into electricity.

In contrast to these other nanomaterials, which were intended for use in photovoltaics that convert light directly into electricity, the hybrid material developed by the UCSD team is being targeted for solar absorption to create heat. The heat is then used to boil water, which in turn creates steam that runs turbines to produce electricity.

The materials that are currently used for solar absorption lack the resistance to high temperatures that the job requires. As a result, they have to be replaced every year. This new hybrid material is unique in that it can withstand temperatures above 700 degrees Celsius.

This should make a significant difference for CSP plants that, as it stands now, have to shut down once a year to remove the degraded sunlight-absorbing material and apply a new coating. Because this means that there is no power generation occurring during this reapplication, the U.S. Department of Energy’s SunShot program was keen to support this most recent research to find a material that would have a significantly longer life span.

With CSP plants already producing approximately 3.5 gigawatts of power globally, the prospect of eliminating an annual shutdown and extending the maintenance interval to several years would make a big difference to the amount of electricity they produce and the confidence people have in this source of electricity.

Dexter Johnson is a contributing editor at IEEE Spectrum, with a focus on nanotechnology.