For the truest of nerds, last December brought a wondrous gift. No, not Star Wars: The Force Awakens. In fact, this gift is just about the furthest you can get from that movie’s hyperrealistic computer-generated imagery and still have something that’s considered screen-based entertainment. I am referring to NetHack 3.6.0, the first significant update in the NetHack game series in over a decade.

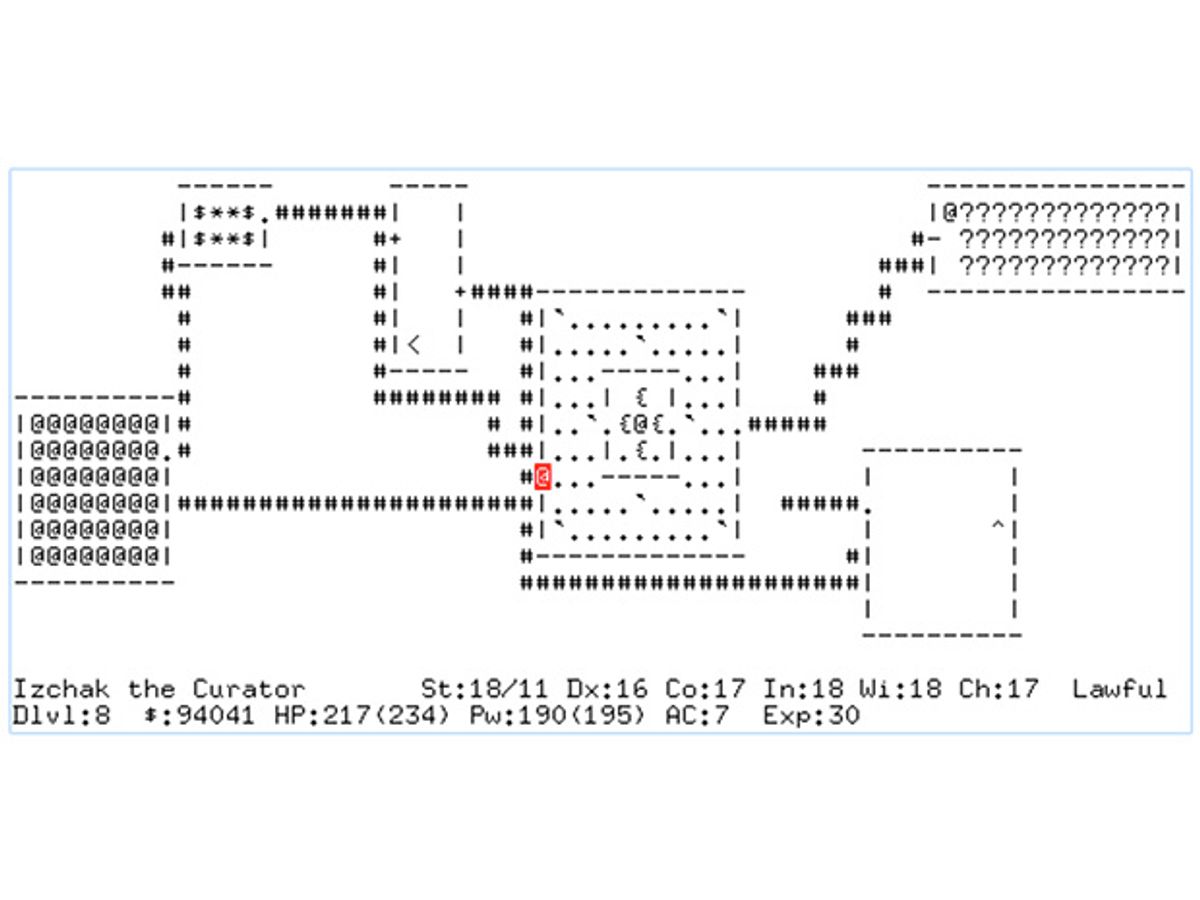

NetHack is free to download and available on many platforms. The goal is to plumb the depths of a procedurally generated dungeon and recover the Amulet of Yendor. Notably, you, the dungeon, and all the creatures and objects within it are represented by simple ASCII characters such as “%,” “>,” and “G” (denoting food, a descending stairway, and a gnome, respectively. Some people have created tile-based graphical interfaces to make things a little more intuitive).

The first version of NetHack was released in 1987 as a heavily modified descendant of a 1984 game called Hack. Hack in turn was based on Rogue, created around 1980 for Unix computers and the simple, character-based terminals of the day. Rogue and NetHack inspired the designers of many later games, in particular demonstrating how procedural generation could greatly extend the enjoyment of a game.

By accreting ingenious and mischievous contributions from programmers over the years, NetHack maintained its popularity thanks to a richness and complexity that belied its simple presentation and hack-and-slash trappings. New versions were regularly released throughout the ’80s and ’90s. But eventually time seemed to have passed it by as even our phones became crowded with games sporting high-resolution color graphics. Now the series has been revived, officially incorporating many modifications created by die-hard enthusiasts. As a tribute to novelist, satirist, and noted NetHack fan Terry Pratchett, who passed away in 2015, the game has also been extensively seeded with quotes pulled from Pratchett’s Discworld book series.

But NetHack 3.6.0 is not the only recent game release to eschew modern 3-D or even 2-D graphics. Here are three other text-centered titles that prize thoughtfulness over pretty pixels.

A Dark Room

Available in both a free online version and as a US $0.99 iOS app, this game has players alternate between reading snippets of text and navigating around a landscape depicted with text symbols, NetHack-style. You are given virtually no information at the outset, learning who your character is and what your purpose is only through exploration. The game is surprisingly good at evoking a subtly disquieting atmosphere that compels the player’s attention. (A prequel called The Ensign, also available, delves more into the player character’s back story.)

Choice of Robots

Available in desktop and mobile versions for $4.99, this is not so much a game as an interactive novel, reminiscent of the old Choose Your Own Adventure books but definitely not written for children. You enter the story as a promising graduate student working on an advanced robot; initial choices center on what you value most in its design and how you are going to deal with your annoying Ph.D. supervisor. Soon, the stakes start rising as war looms. As with the best interactive fiction, Choice of Robots is very good about putting you on the horns of dilemmas, with downsides and upsides to every choice.

Lifeline...

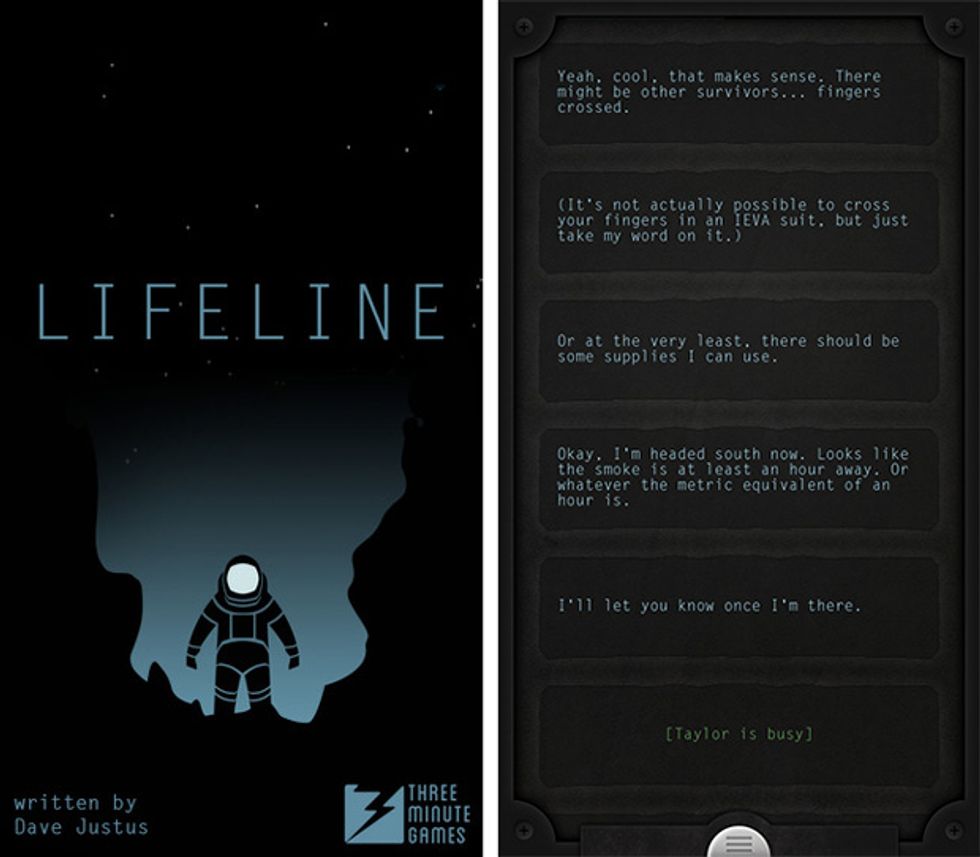

Optimized for use with the Apple Watch but playable with just an iPhone or iPad, this 99-cent game makes the unusual but effective choice of putting you at a considerable remove from the action. Your role is as an advisor for Taylor, an astronaut trainee who has crash-landed on an alien planet. Taylor’s only link to the outside world is through text messages, which he uses to describe what’s going on and ask questions about what he should do as he struggles to survive. Another unusual but effective game design choice is to have users play the game in real time, so once Taylor goes off to perform some action, he won’t message you again till he’s done, whether that takes seconds or hours, effectively building tension as you go about your real-life day, waiting for his signal. A sequel is now also available.

This article originally appeared in print as “Return of the ASCII.”