Techno Cops: Los Angeles Sheriff's Department Explores Less-Lethal Options

The LASD is creating a test bed for advanced police technology

It’s a clear, cool morning, a perfect day for hiking or sailing or just about anything except what I’m doing, which is standing in the parking lot of a strip mall in East Los Angeles. Strip malls are never lovely, and this one only reinforces the stereotype: a squat and sleepy line of stuccoed buildings, whose tenants reflect a cross-section of life on the margins—Dutch’s Liquor, Ernie’s Escrow, T’s Check Cashing, a bar called The Bear Pit.

But today there’s an uncharacteristic buzz in the air. Word has it that two robbery suspects have taken a woman hostage and are now holed up inside. The police have been notified, and a SWAT (short for Special Weapons and Tactics) team from the Los Angeles County Sheriff’s Department (LASD) is suiting up to intervene.

Because the suspects’ exact location is unknown, they decide to send a robot fitted with video cameras into the liquor store, to survey the scene. The officers also use a camera on an extending pole to peer into the windows. In a second-story room, they spot one suspect holding a knife to the hostage’s throat. The officers negotiate by phone, and sensing he’s outnumbered, the suspect readily agrees to surrender and set the hostage free.

The second suspect isn’t coming out, though, and so the six-member SWAT team goes in. There’s a minimum of chatter as their well-choreographed maneuvers take them quickly up the stairwell to the attic, where the suspect is thought to be hiding. Once again, the pole-mounted camera is deployed, this time to survey the attic, periscope-style. It’s dark, so the camera automatically switches to infrared mode. There he is, crouched under the eaves.

The suspect doesn’t see the camera and is disconcerted when the officers begin ordering him about. “Put your hands on your head! Both hands! That’s better.” Like his friend, he readily agrees to surrender. The officers are armed with MP5 submachine guns and Beretta pistols, and they’ve brought along an array of nonlethal weaponry, too. But they won’t be needing any of those items—this time.

Bystanders look on as the SWAT team and suspect emerge into the parking lot. It’s a little anticlimactic, accustomed as we are to Hollywood shoot-’em-ups. But for the LASD deputies, the rescue counts as a “save.”

Aggressive exploration

Or rather, it would have if this had been real. In fact, though, the morning’s event was staged for a British TV crew from the Discovery Channel and a couple of print journalists. The hostage rescue played out much like real-life ones, the deputies reassure me—except for maybe the smoke machine, its fog helping accentuate the green glow of the team’s light-emitting diode (LED) flashlight and the red laser beams on their gun sights. The shabby strip mall is actually the department’s Laser Village Training Center.

The reason I’m here is that the LASD, aside from having one of the oldest, most active, and most decorated SWAT squads in the world, has undertaken an innovative technology development project. It’s the brainchild of Captain Charles (“Sid”) Heal, who heads up the department’s Special Enforcement Bureau, which includes the SWAT squads, as well as search and rescue, police dogs, mounted police, emergency services, and a motorcycle detail.

With only 8900 deputies to police some 10 500 km2, an area bigger than the states of Delaware and Rhode Island combined, the LASD has long relied on helicopters, motorcycles, and other technical means to gain an upper hand. Heal’s project, though, is distinguished by its aggressiveness in seeking out new technology. His six-man technical-assault SWAT team scouts out new equipment; they travel extensively to visit companies and attend conferences. Once they’ve selected a device, they test and evaluate it in the field, working closely with the vendors and tech developers and giving feedback as the prototypes go through design iterations. Only the most useful and affordable get adopted.

The nonstop vetting and analyses have turned the Special Enforcement Bureau into a kind of international test bed for new law enforcement technology. Each week, Heal’s office fields a handful of inquiries from police departments around the country and even overseas. “We got a call the other day from somebody who wanted our complete equipment list, everything we use,” says Scott Walker, a SWAT team leader.

But why do cops need the kind of hardware more generally associated with sophisticated military invasions? “The fact is, the crooks have reached parity with us,” Heal says. He cites a recent incident in the northern part of the county, where a gang was making and dealing methamphetamine. The gang’s leader had “assault weapons, night scopes, and underground pressure-activated alarms, and he swore that he’d never be taken alive,” Heal recalls. Though the LASD managed to arrest the leader and dismantle the drug lab, he adds, “my great fear is that we’re going to end up in a big gunfight with only the same tools as the suspects.”

And in an era when the usual suspects include international terrorists and when even small-time drug runners tote machine guns, the ideas and technologies flowing from Heal, his crew, and his contractors seem to portend a critical departure for big-city law enforcement. The vision extends far beyond improving discrete weapons and tools: the team is now evaluating the first pieces of an advanced system that they hope will one day let them quickly and seamlessly fuse data from robots, cameras, sensors, and street cops into a virtual-reality crime scene, accessible to officers, commanders, and outside experts no matter where they happen to be. “In this day and age, why are we physically moving the bodies when all we need to move is the information?” Heal asks.

A cop, marine, and scholar

A 27-year veteran of the LASD, Heal has served in virtually every function there, including investigation, patrol, SWAT, emergency operations, and administration. He also served with the Marine Corps and its reserve for 33 years, doing tours in Vietnam, the Gulf War, and Somalia, where he was the principal advisor for nonlethal options in Mogadishu. That’s how I first found out about him: a senior researcher at Rand Corp. (Santa Monica, Calif.) had told me that Heal is “one of the world’s true experts” in nonlethal weaponry. Intrigued that a think-tank analyst would refer me to a police officer, I gave Heal a call.

It soon made sense. In addition to his police and military work, Heal (pronounced “hail”) has an academic streak, with a wall full of degrees—a B.S. in police science and administration from California State University at Los Angeles, a master’s of public administration from the University of Southern California, and an M.S. in management from California Polytechnic University at Pomona—and an extended publications list (see a selection at https://www.urbanoperations.com/heal.htm) to show for it.

Heal is, in other words, someone who has walked the walk. That may explain why he seems to be uniformly admired and respected by his staff. “He’s got a couple of master’s degrees, but he’s able to operate at my level as well,” SWAT deputy Dan Nathan told me. “He’s one of these guys who—every little thing that he’s ever seen or ever heard—it stays with him.”

Heal’s also just a very engaging person. Muscular, with close-cropped sandy-blond hair, the father of five laughs easily and talks a blue streak. In our several conversations over the course of a year, he nearly always had a detailed, ready, and often humorous answer to a question, and when he didn’t have an answer (as when I asked the weight of the equipment that the average deputy carries), he always got back to me (answer, e-mailed three days later: “18 pounds with nylon web gear and 20 pounds with leather gear,” followed by an itemized list).

Heal was never cagey or defensive, even when questioned about the more controversial aspects of police work, like crowd control. In fact, for a law enforcement type, he holds some fairly radical opinions about public protests; he sees them as valid forms of expression and necessary release valves for social unrest. “The Boston Tea Party was by anyone’s definition a riot,” he declares.

Technology scouts

Heal’s technology exploration project got started in 1997. At the time, he was primarily interested in nonlethal weapons, like beanbag launchers, stun guns, and pepper spray, which cause pain and temporary disorientation, but seldom death. Heal himself prefers the term “less lethal,” because people have been killed with nearly all such devices.

The bureau’s interest in nonlethal technology was understandable. “Most of our operations are focused on resolving things without the use of lethal force,” Heal says. Last year, only 1 percent of the SWAT call-outs—the profession’s term for their response to an unplanned event like a suspect barricaded in an attic—ended with them killing the suspect.

The problem is, Heal says, “there’s not a single device out there that doesn’t have major shortcomings.” He considers the M-26 advanced taser from Taser International Inc. (Scottsdale, Ariz.) to be among the best nonlethal weapons on the market. Pulling the trigger breaks a gas canister, which in turn discharges two barbed darts, each trailing a wire that’s connected to either the positive or negative electrode inside the gun. Current from the gun’s eight AA batteries travels down the conductive wires and into the target’s body, which, being likewise conductive, completes the circuit.

The M-26 can deliver a 5-second jolt of up to 50 000 V. The shock has the effect of tetanizing skeletal muscle while leaving other types of muscle, like the heart, alone. It’s said to be a pain like no other. Heal himself has been zapped, once, as have most of his deputies. “The first time you’ll do it out of curiosity,” he says, grinning. “The second time you do it out of stupidity.”

But the taser is far from ideal. Its wires don’t quite go six and a half meters, so if a suspect is standing 3 cm farther off, or wearing a puffy jacket, it’s useless. What’s more, it only has one shot, and after the darts puncture the suspect’s skin, he or she needs to be taken to the hospital to get them removed.

In pursuit of the perfect nonlethal weapon, Heal and an assistant traveled extensively, attending conferences and industry shows and visiting vendors. They also scoured whatever literature was available. “We had to hunt for this stuff,” Heal recalls. “You couldn’t just order it from a catalog.” Much of what they found was not intended for law enforcement. Some products were built for the military; one device, an infrared detector called a Life Finder, was sold to deer hunters.

Adapting such products to the very specific needs of the LASD would take time and money. But Heal’s team had no money, so instead they struck a deal with the developers: give us the unit for free and we will field-test it and work with you to adapt it for the law enforcement market.

He proved an extremely competent project manager. The evaluations and field tests his staff did were backed up by thorough documentation and candid feedback. On the department’s intranet, Heal set up a database to track the status of every device and system under consideration. There’s also an online workshop on product development for anyone who has an idea to pitch and a tutorial on how to evaluate new technology. As part of the bargain, Heal agreed to help publicize any successful products that resulted from the collaboration.

That’s more than simple publicity-seeking. Introducing technology inevitably carries both good and bad consequences, he says, and so he goes out of his way to speak with community groups. He respects their right to question the adoption of any new weapons or surveillance technology. “You don’t get the amount of law enforcement you can afford,” Heal says. “You get the amount that you can tolerate.”

Opportunity knocks

Not every company leapt at the chance to spend months or even years doing extra R and D for a client who couldn’t pay, but a few did. Defense contractor Chang Industry Inc. (La Verne, Calif.) was one of the first. “They’re so enthusiastic—definitely not grant chasers,” Heal says. “They have an allegiance to the technology.”

Over the years, Chang has presented Heal with a number of prototypes, some far out, some less so. Heal recalls one visit to the Chang offices. “They had something new to show me, but it was midnight when I finally got there,” Heal says. “The lights were on, and they were still working on it, and they were all excited, like a bunch of kids.” The device was a small digital video camera connected to a radio transmitter, so that images could be viewed from afar.

The camera, which Heal’s team dubbed the Chang Eye, has gone through several iterations since then. It’s now about the size of a deck of cards, runs on three AA batteries for four to five hours, and can be surreptitiously placed on a window or under a door, sending its signal back to a remote viewing screen at 900 MHz in the ISM band (a band reserved mainly for nonregulated industrial, scientific, and medical use). It also operates in low light, making it a cheap alternative to night-vision cameras, which capture images in the infrared. The bureau does have a few pieces of night-vision equipment, but the best technology is still too expensive for widespread use.

For the sheriff’s demo in East L.A., engineers from Chang’s nonmilitary division have brought along a couple of new toys. The first is a remote-controlled mini-helicopter with a video camera affixed to its body, to hover and look in windows. Its two-stroke engine whines like a leaf-blower and leaves behind a blue-gray exhaust trail.

After several turns around the parking lot, the craft veers too close to the building and hits the roof with a sharp crack. It falls to the pavement, spinning madly until someone grabs it and kills the engine. Heal had been skeptical about the helicopter all along, and the engineers now look sheepish. Later, though, they redeem themselves with a toy car that uses a video camera to check the undersides of parked cars and trailers, under porches, and in crawl spaces.

Seal of approval

When Heal was promoted to captain and head of the Special Enforcement Bureau in January 2001, he opened up his technology development project beyond nonlethal weapons to include anything useful to the bureau. He assigned the SWAT “blue” team to be his technical-assault squad. Though this squad still trains and operates just like the other five SWAT teams, its members are also responsible for deploying robotics and electronics equipment as needed, and for scouting out and evaluating new products.

Heal explains: “We look for things like, is it user-friendly? Easy to deploy? Are the knobs sturdy? Is it durable in hot and cold? In the rain? How do we carry it? What’s the battery life?” That last point has proved a perennial stumbling block. Many of the products were intended for the military, and their power sources tend to be exotic and costly, albeit lighter or more efficient.

The bureau’s needs are different. “Most of the things these guys do are in odd places at odd times,” Heal explains. “And policemen are so notoriously poor at maintenance, we can’t count on having fully charged batteries. So we’ve limited our developers to using power sources that we can get at a Rite Aid drugstore at midnight.” The ideal solution, he says, “is to be able to plug into the wall, a car cigarette lighter, or a car battery—to have three or four possible power sources.”

One of the biggest successes is the pole cam. It’s just what it sounds like: a video camera on the end of a long pole, tethered to a 13-cm-diagonal viewing monitor. It’s used in places where sticking your head up—to look in a crawl space, say—may be the last thing you do with it.

In the two years the bureau has been evaluating the pole cam, it has asked the developer, Lamsa Weapons Systems (Los Angeles), to make a number of refinements. “This little metal piece here was our idea,” says blue team leader Scott Walker, pointing to an 8-cm-long tube extending above the camera. “It pushes the ceiling tile up.” They’re also looking at adding a spring-loaded punch for breaking windows.

“This is one of those devices that’s been technologically available for a long time, but nobody had figured out the application,” Heal says. “The monitor, the camera—all this stuff is off the shelf. The newness is in how the developer configured it.”

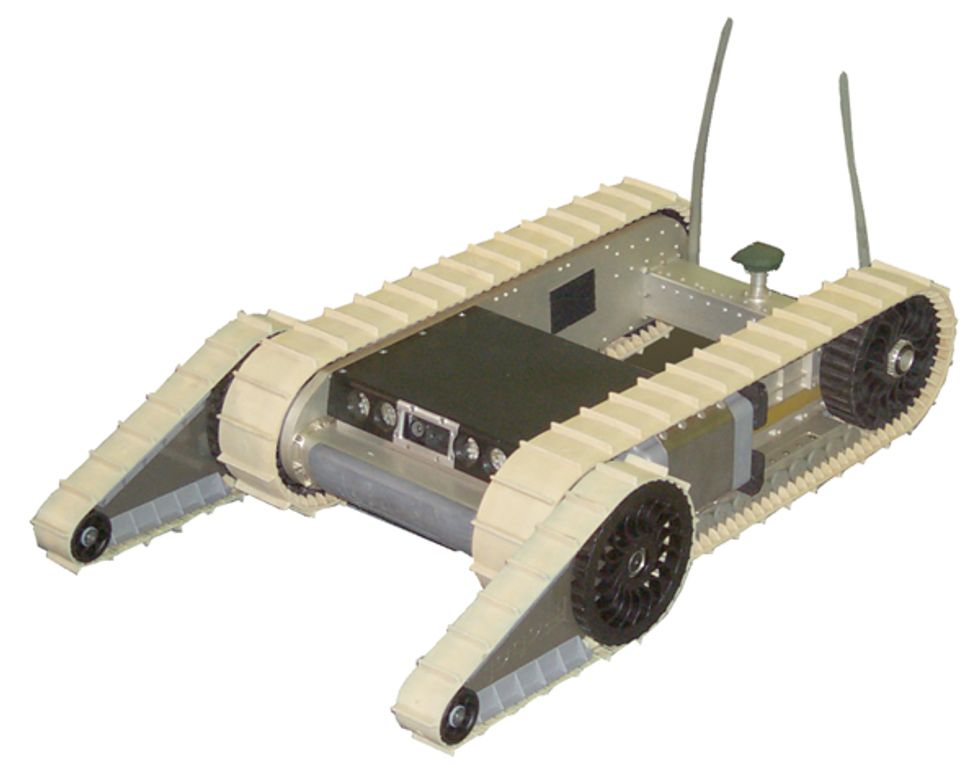

As Heal’s technology exploration project progressed, word got around, to the point where having the LASD evaluate a product carries something like the police equivalent of a Good Housekeeping Seal of Approval. “A lot of others look to them—‘If they’re using it, then I’ll buy one,’” says Gordon Krueger, a former mechanical engineer at iRobot Corp. (San Luis Obispo, Calif.), whose PackBot robot was one of several at the sheriff’s demo. “So that’s a selling point for us, that the LASD is using our robots.”

Dru Murphree, a senior engineering technician at Mesa Associates Inc. (Madison, Ala.), which has given the bureau one of its portable Matilda robots, agrees. “Sid’s been very useful at telling us what payloads to develop, and just moving us in useful directions,” he says.

Heal encourages vendors to collaborate, which explains why representatives from two rivals like Mesa and iRobot are willing to discuss their products within earshot of one another. “We’ll get the vendors together, introduce them, share the information, and encourage them to cooperate,” Heal says. “We don’t sign confidentiality agreements with anybody.”

The big picture

Looking farther out, the bureau is hoping to network many of its technologies into a so-called ground video link system that would give everyone at the crime scene and on up the chain of command a common operational picture, “so that everyone’s reading from the same sheet of music,” as Robert Alcaraz, a recently retired bureau sergeant, put it. In current practice, everyone with decision-making authority must travel to a central command post. It’s a time-consuming process, and the commanders often operate on limited information that’s been phoned or radioed in. “When people actually arrive on the scene, having only discussed it by phone or radio, they say, ‘This is nothing like what I imagined,’” Alcaraz explains.

As envisioned, the system would connect deputies’ PDAs and laptops to a secure Internet site accessible by command headquarters. Audio and video signals from the pole cams, robots, microphones, thermal imagers, and other surveillance devices at the crime scene would be available to all. There would also be a so-called virtual reachback feature, so that, for example, a chemical weapons expert could log in from wherever he or she happens to be. “They can detect subtle differences that others miss,” Heal says.

As a first step, several developers have built prototypes of a cyber command post. The blue team has already field-tested two of them, from Lamsa and from CGI Group Inc. (Montreal) and at press time was awaiting delivery of two others, from The Millennium Group Inc. (Franklin, Tenn.) and from Aegis Assessments Inc. (Newport Beach, Calif.).

The Lamsa prototype, featured at the tech demo, is built around a rapidly deployable surveillance system, or RDSS, a wireless video system that’s popular at nuclear power plants. The whole system, which is controlled from an off-the-shelf laptop and relies on an IEEE 802.11b link, takes about a half-hour to set up. From the laptop, the field commander can pan, tilt, and zoom the RDSS’s three cameras, perched around the strip mall. Images from a Chang Eye camera affixed to a window are also displayed. From their PDAs, the SWAT team can view those same images, refreshed in near real-time.

Ideally, Heal says, it should take just one person no more than 15 minutes to deploy the cyber command post; the signals will need to travel up to 1.7 km through buildings and other obstructions. The next step will be to link it to an extranet, to deliver crime scene data to those farther away.

Moving ahead

Despite the Special Enforcement Bureau’s growing reputation, the idea of cops as innovators continues to jar people, even within the department. At Heal’s first staff meeting after taking over the unit, one commander mocked the SWAT teams’ computer skills. “He said, ‘We lost ’em as soon as the screensaver moved!’” Heal recalls. “Everybody laughed because nobody could imagine these Neanderthals, as he put it, using technology. I told him, ‘In a year, you’re going to say that and nobody’s going to understand the joke.’” The commander, Heal notes with pleasure, “has become one of our strongest supporters.”

Those outside the department are also taking note. Recently, a concerned citizen who happens to be a billionaire heard about Heal’s program and gave US $185 000 to underwrite it; the first $50 000 will go toward infrared sensors that will feed into the ground video link system.

It’s still an uphill battle, Heal says. The LASD recently cut a number of programs and some staff, to cover a $100 million budget shortfall—not a climate conducive to deploying new technology. A lot of times, assessments are based on how the last call-out went, he adds. “They’ll say, ‘Nobody got shot at the last time, so why do we need this robot?’ But we’re supposed to be forward thinking. Our culture has to change.”

This article appeared in the December 2002 print issue as “Techno Cops.”

To Probe Further

How experts in artificial intelligence (AI) create intelligent game objects and characters is explained in a collection of articles in AI Game Programming Wisdom, edited by Steve Rabin (Charles River Media, Herndon, Va., 2002).