Less is more when it comes to beef on the bun (at least according to your doctor), and the same now appears to be true for AC voltage. Research by the Electric Power Research Institute (EPRI), in Palo Alto, Calif., is confirming that many electrical devices work equally well and use less energy at lower voltages, and that offers utilities a big conservation opportunity. By trimming the voltage they deliver, distribution utilities in the United States could slim the nation's power appetite by 3 percent—the equivalent of unplugging every refrigerator in the country—according to an August 2010 analysis from the Department of Energy's Pacific Northwest National Laboratory (PNNL) (PDF).

Some utilities are facing push-back from consumers disenchanted with smart meters and riled by real-time pricing for electricity. So the best news for utilities is that such conservation voltage reduction, or CVR, should cut energy use without asking consumers to change their behavior. CVR can also help stabilize the grid.

CVR operates within the wiggle room offered by electrical standards. The standard for the nominally 120-volt AC power in the United States and Canada, for example, calls for 114 to 126 V. The range is practical, given the ever-shifting power demand on a distribution system. Utilities generally measure and control voltage at their substations and aim for the higher end of the range to avoid browning out customers at the ends of the lines. The result is that, on average, U.S. customers get 122.5-V power.

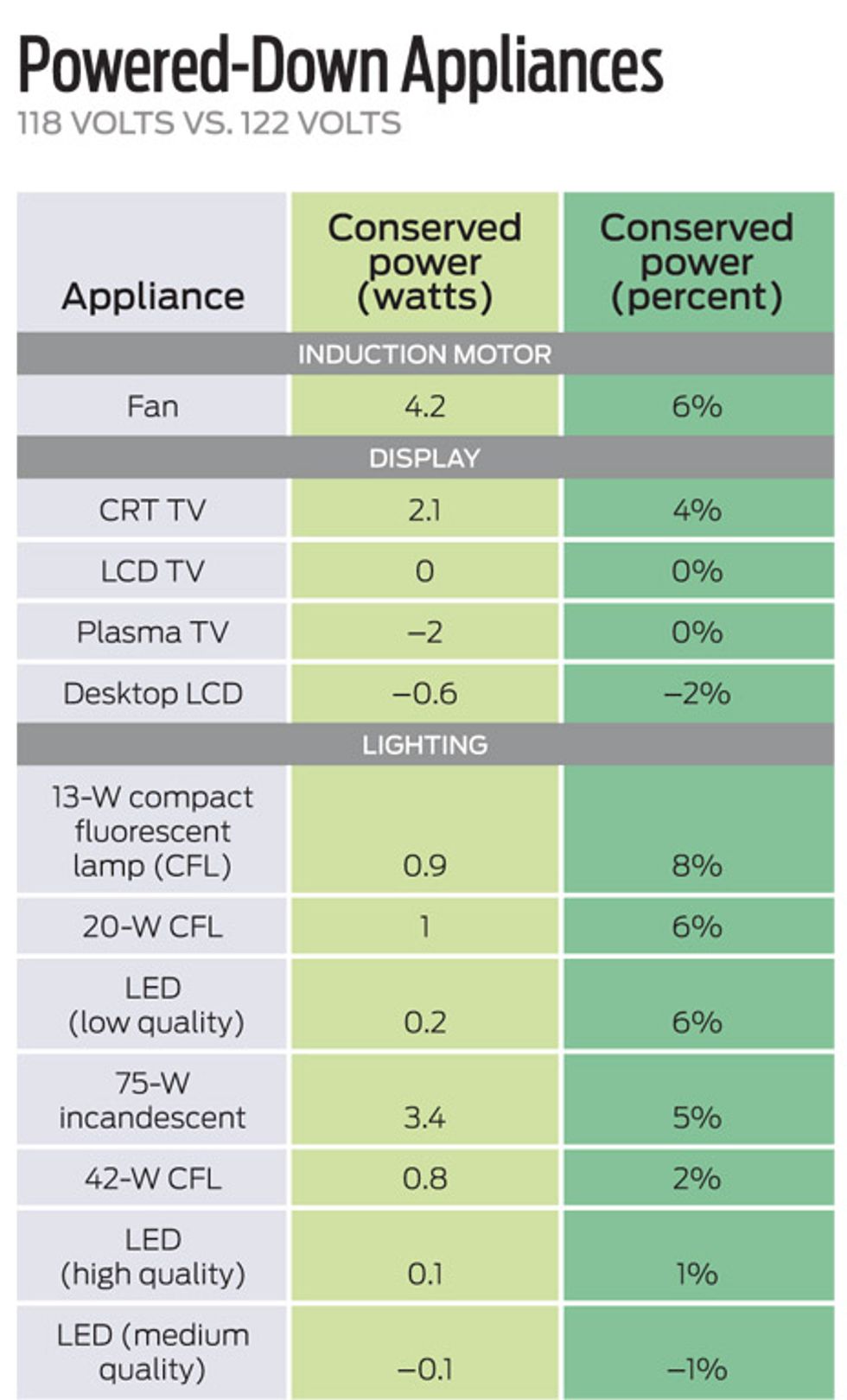

Until recently, most utilities saw no need to operate differently, assuming that voltage had a negligible effect on power demand. And indeed that assumption is true for some loads. Electric heaters on a lower voltage simply run longer to deliver the same heat, resulting in no savings. But other appliances can get by at lower voltages by doing less work. For example, at the low end of the voltage range, lights dim imperceptibly.

The big-ticket item for CVR appears to be the induction motors in fans, refrigerators, and dozens of other appliances. Motors tend to operate at a lower mechanical load than they are rated to handle. As a result, higher voltages generate stronger magnetic fields than the motors can use, throwing energy away.

Utilities in the U.S. Pacific Northwest began testing CVR's potential in the 1990s. They minimized the voltage delivered by measuring it close to the consumer and adjusting frequently. Voltage is controlled at substations for each feeder line, which generally serves a whole neighborhood. An influential 2008 study by the Northwest Energy Efficiency Alliance, based in Portland, Ore., analyzed the experience of six CVR pioneers and found that on average every 1 percent drop in voltage delivered a 0.7 to 0.8 percent drop in power. And most feeders could safely drop 3 to 4 V.

Bob Uluski, a distribution specialist with EPRI, says many utilities are exploring CVR through pilot projects financed with economic recovery funds, and a few, such as Progress Energy, in Raleigh, N.C., are pushing into full-scale implementation. For those installing smart meters, CVR is a natural, because smart meters provide the real-time voltage readings to guide the voltage trimming: If levels dip too low, many smart meters can send an alert back to the utility. However, even with smart meters, utilities will be adjusting the voltage feeder by feeder, not at the level of the individual house.

Uluski says EPRI is developing more precise tools to help utilities predict how much energy CVR can save them on each feeder. That should help focus CVR investments, according to the PNNL report. The report's model suggests that using CVR on the 40 percent of feeders most responsive to it nationwide would capture 80 percent of the technique's energy-saving potential. EPRI is also quantifying how emerging loads such as plasma TVs and electric cars will respond to CVR.

The biggest obstacle to CVR, however, remains the classic lost-revenue problem that has long stifled utilities' conservation impulse. Utilities that succeed at CVR will sell less power. Tom Wilson, president of CVR system developer PCS UtiliData, based in Spokane, Wash., says this lost revenue problem has made selling utilities on CVR an "uphill struggle."

Wilson says change is coming, as regulators get more creative about rewarding utilities for the "nega-watts" of energy saved through conservation programs. Rather than wait, he says PCS is marketing CVR to large power consumers such as industrial firms and universities. They have the clout to press utilities to implement CVR on their feeders, says Wilson.