On 2 September 1945, representatives of the Japanese government signed the instrument of surrender on the deck of the USS Missouri, anchored in Tokyo Bay. So ended perhaps the most reckless of all modern wars, the outcome of which was decided by U.S. technical superiority even before it started. Japan lost in material terms even before it attacked Pearl Harbor: In 1940 the United States produced roughly 10 times as much steel as Japan did, and during the war the difference grew further.

The devastated Japanese economy did not surpass its prewar peak until 1953. But by then the foundations had been laid for the country’s spectacular rise. Soon its fast-selling exports ranged from the first transistor radios (Sony) to the first giant crude-oil tankers (Sumitomo). The first Honda Civic arrived in the United States in 1973, and by 1980, Japanese cars claimed 30 percent of the U.S. market. Japan, totally dependent on crude-oil imports, was hit hard by the OPEC oil price rises of the 1970s, but it adjusted rapidly by pursuing energy efficiency, and in 1978 it became the world’s second largest economy. By 1985 the yen was so strong that the United States, feeling threatened by Japanese imports, forced its devaluation through the Plaza Accord. But even afterward the economy soared: In the five years following January 1985 the Nikkei index rose more than threefold.

It was too good to be true; indeed, the success reflected the working of an enormous bubble economy driven by inflated stock and real estate prices. In January 2000, ten years after its peak, the Nikkei was still at only half its 1990 value, and only recently has it risen above even that low mark.

Once-iconic consumer electronics manufacturers like Sony, Toshiba, and Hitachi now struggle to be profitable. Toyota and Honda, global automotive brands once known for their unmatched reliability, are recalling millions of vehicles. Takata’s defective air bags recently resulted in the biggest recall of a manufactured part ever. And Yuasa made unreliable lithium-ion batteries for the Boeing 787. Add to this the rapidly changing governments, the March 2011 tsunami followed by the Fukushima disaster, and worsening relations with China and South Korea, and you get a worrisome picture indeed.

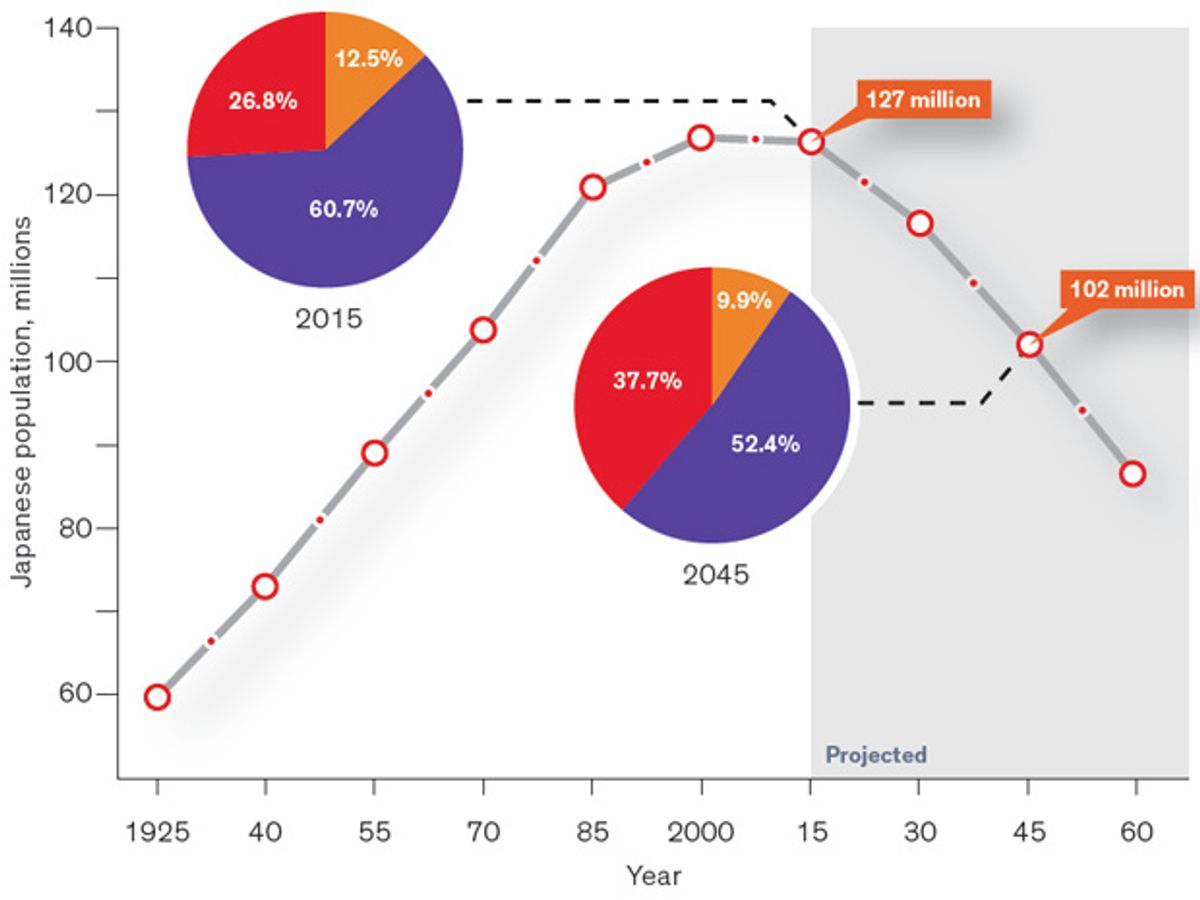

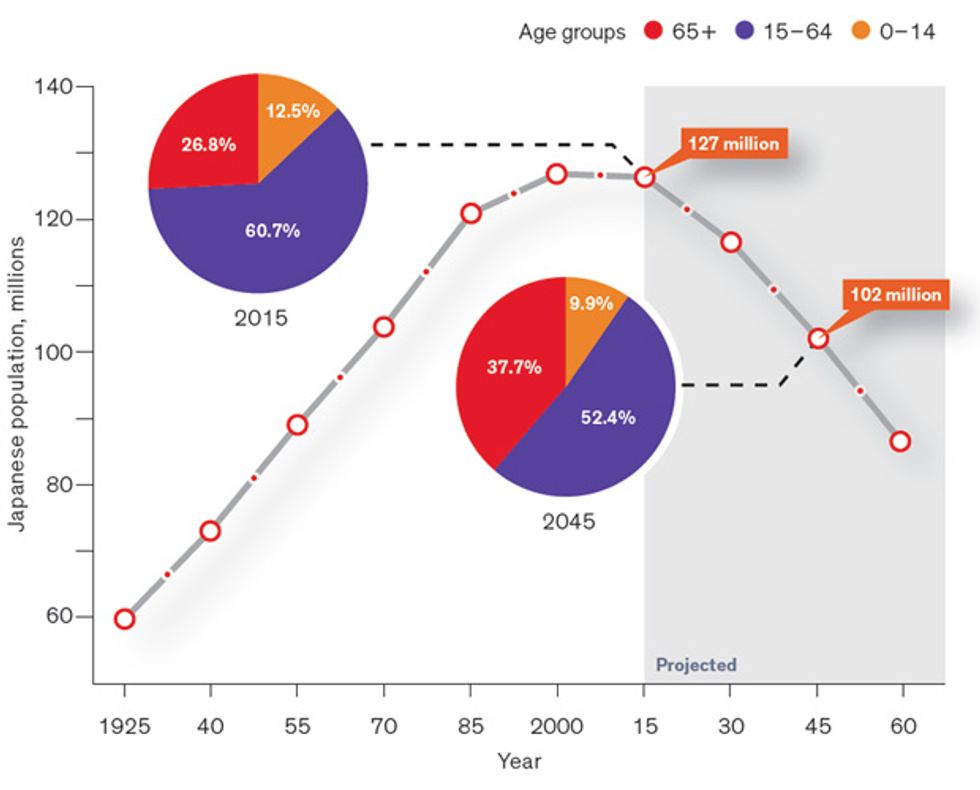

But in the long run the fortunes of nations are determined by population trends. Japan is not only the world’s fastest-aging major economy (already every fourth person is older than 65, and by 2050 that share will be nearly 40 percent), its population is also declining. Today’s 127 million will shrink to 97 million by 2050, and forecasts show shortages of the young labor force needed in construction and health care. Who will maintain Japan’s extensive and admirably efficient transportation infrastructures? Who will take care of millions of old people? By 2050 people above the age of 80 will outnumber the children.

Fortunes of all major nations have followed specific trajectories of rise and retreat, but perhaps the greatest difference in their paths has been the time they spent at the top of their performance: Some had a relatively prolonged plateau followed by steady decline (both the British Empire and the 20th-century United States fit that pattern); others had a swift rise to a brief peak followed by more or less rapid decline. Japan is clearly in the latter category. Its swift post–World War II ascent peaked in the late 1980s, and it’s been downhill ever since: in a single lifetime from misery to an admired—and feared—economic superpower, then on to the stagnation and retreat of an aging society.

This article originally appeared in print as “ ‘New Japan’ at 70.”