Before the Fukushima Dai-ichi nuclear accident of 2011, Japan was the third largest producer of nuclear power in the world. Its 54 reactors had a capacity of about 50 gigawatts. Now the Japanese government is contemplating whether it can scale down from 50 GW to zero by 2040 without crippling its economy in the process.

A government policy paper [PDF] released in September called for the elimination of all nuclear power by 2040, and public opinion polls have shown that the majority of citizens favor a phaseout. But the matter is far from settled: The policy paper elicited strong protests from business groups, and consequently the Cabinet, the executive branch of Japan’s government, declined to endorse the zero-nuclear goal.

Here are the sticking points in the ongoing debate over whether Japan can eliminate nuclear power.

How to Phase Out Nuclear

After the Fukushima disaster, all the country’s reactors were shut down for safety checks, and only two have been allowed to resume operations. The government has assumed that many more will be declared safe and restarted despite local opposition.

The government’s September policy paper proposes two rules regarding nuclear power: It suggests a maximum 40-year life span for all reactors and states that no new nuclear construction should be permitted. Sticking to those two principles, the phaseout can be done largely by attrition, says Yugo Nakamura, a Tokyo-based analyst for Bloomberg New Energy Finance. “Assuming that all the reactors retire after 40 years of operation, then as of 2040 there will probably be only five reactors still up and running,” he says. And with only 40 years to recoup a huge investment, even if there was no ban on construction, there’d be no money to be made in building new reactors, he adds.

False Hopes for Energy Conservation?

The government is expected to call for an overall reduction in electricity use: One policy document [PDF], issued in July, assumed usage of 10 percent below 2010 levels. Yet thus far the government has released no detailed proposals.

The nation did respond well to the government’s call for voluntary cuts in electricity use throughout the past two summers, when energy use peaks. But David Rea, a consultant with the firm Capital Economics, argues that conservation may not be a viable solution. The main reason Japan made it through without shortages last summer was “weakness in the economy,” he wrote in a recent report. Therefore “a false picture was created of whether a prospering, growing Japanese economy can exist without nuclear power.”

Imported Fossil Fuels

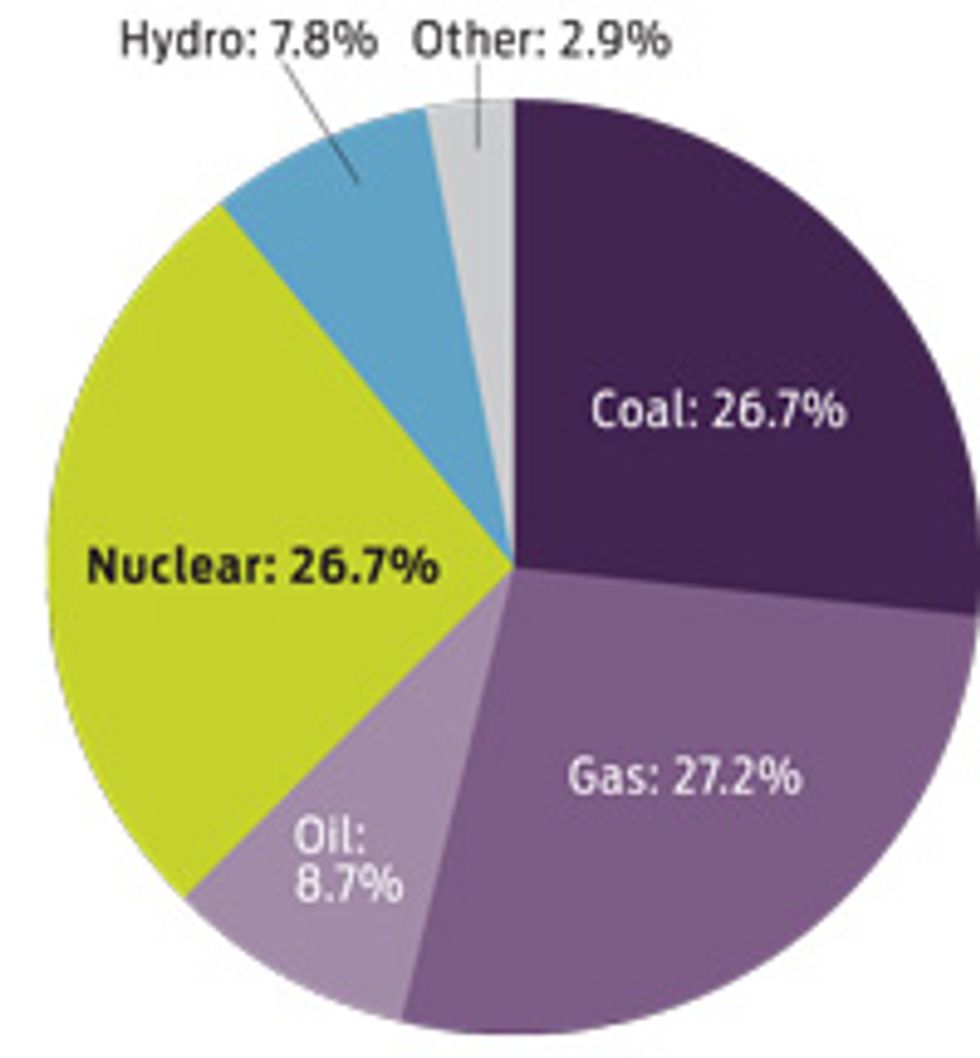

When Japan’s fleet of nuclear reactors shut down, the nation’s utility companies fell back on power plants fired by coal, oil, and natural gas to provide base-load electricity. These power stations have kept the lights on, but at a cost; some utilities have already raised electricity prices to pay for fuels, which are mostly imported. If Japan shifts away from nuclear, fossil fuels are expected to fill the gap. The government has suggested that utilities decrease the share of coal and increase the share of natural gas to keep carbon dioxide emissions down.

Can Renewables Ramp Up?

Japan’s biggest energy challenge is scaling up its renewable power sector in a hurry. In 2009, renewable energy supplied 11 percent of the country’s electricity, with most of that coming from hydroelectric stations. The government made a start on boosting this fraction last year when it passed a feed-in tariff law to guarantee profitable electricity prices for renewable energy projects; early indications are that this law is stimulating new investments. Andrew DeWit, a professor of economic policy at Rikkyo University, in Tokyo, says that in just two months, applications were filed for 72 680 renewable projects totaling 1.3 gigawatts. Most of these projects are small rooftop solar installations, but a few are utility-scale solar or wind farms.

Japan has been slow to develop its solar, wind, and geothermal resources in large part because the energy sector is dominated by the “Big 10” regulated utilities, which had invested heavily in nuclear. But DeWit says that every time a local government or bank funds a renewable energy project and benefits from the new tariff law, pressure grows to deregulate the industry. “It’s giving them incentives to push for restructuring of the power sector, because they’re invested in so much [renewable] capacity,” he says. The government is now discussing how to “unbundle” the generation and transmission sectors to make conditions more favorable for renewable energy.