Wind Power in Paradise

How an international team of engineers brought wind power to the Galápagos Islands

A gentle breeze blows across the harbor of San Cristóbal, the easternmost island in the Galápagos archipelago. Sea lions bask on the beach under the equatorial sun, and blue-footed boobies dive for anchovies in the Pacific waters. A round brown finch swoops down from a prickly-pear cactus, flutters in midair for an instant, and then lands on my head.

Tens of thousands of tourists come to the Galápagos Islands each year to get close to its extraordinary fauna—to snorkel with hammerhead sharks, hang out with giant tortoises, and have their scalps inspected by Darwin’s finches. The archipelago’s exquisitely unique creatures gave Charles Darwin a good deal of inspiration for his theory of evolution when he visited in 1835. Nature-loving visitors now flock to the islands in hopes of seeing what Darwin saw.

Ironically, the influx of ecominded tourists now threatens this island paradise. In particular, the huge demand for electricity to power hotels, shops, and restaurants, as well as the homes of permanent residents, has placed an enormous burden on the islands’ power grid, which until recently relied entirely on diesel generators. In 2007, about 5 million liters of diesel fuel had to be shipped in from the mainland to keep the generators running, and demand is growing 10 percent each year.

Seven years ago, after a tanker ran aground and spilled more than half a million liters of fuel into San Cristóbal’s harbor, the government of Ecuador, which governs the islands, intensified efforts to free the Galápagos from fossil fuels. A like-minded group of United Nations officials, power engineers, and government representatives came together to devise an energy scheme for the islands, based on renewable energy.

To realize their goal, they had to overcome unexpected technical and logistical hurdles, ease environmental concerns about their project’s potential impact on the fragile ecosystem, and cut through the inevitable bureaucratic red tape. There were moments when even the project’s leaders feared it would never happen. But this past fall, the team finally installed three enormous wind turbines in the San Cristóbal hills, capable of supplying half the island’s electricity.

“This is one of the biggest wind-diesel hybrid projects in the world,” says Luis Vintimilla, an Ecuadorian engineer and one of the project managers. “We hope it will be a model for other islands in the Galápagos and elsewhere.”

ON A SERENE afternoon last September, I head to the highlands of San Cristóbal with Jim Tolan, an American engineer who, along with Vintimilla, manages the project.

“The place we’re going, it’s called El Tropezón Hill. I think that means ‘big stumble,’ so watch out,” Tolan quips as we hop into a Chevrolet pickup. “Oh, and grab your rain jacket.”

We drive up a dirt road, and the coast’s arid, volcanic landscape metamorphoses into steep, grassy hills dotted with Miconia robinsoniana, a leafy shrub with purple flowers that you won’t find anywhere outside the Galápagos. A dense white mist suddenly engulfs our vehicle. The blue sky disappears, as do the road and the hills. It’s like riding through a cloud. Tolan explains that this is the garúa season: cold winds and ocean currents cool the air, and a heavy fog and drizzle—the garú— forms in the highlands.

We park, and only after I get out of the truck do I realize we’re standing next to a steel tower as tall as a 15-story building, topped by a three-bladed rotor. Two identical towers perch nearby. Erected a month ago and now beginning operation, they are state-of-the-art wind-power turbines imported from Spain. Through the dense fog, I can barely make out the blades—each about the length of a jumbo 747 wing—but I can hear them turning with a thunderous, cadenced whoosh.

The presence of massive wind turbines in the Galápagos may sound incongruous, but as any visitor quickly realizes, the islands are no longer the deserted paradise that first captured Darwin’s imagination more than 170 years ago. Today the archipelago, which consists of 13 main islands and numerous islets and rocks, is home to more than 20 000 people, most of whom work in tourism or subsist on fishing and farming. An additional 120 000 visit annually, and that number continues to swell each year.

One result of all this human activity is a higher demand for electricity. The diesel generators on the four inhabited islands burn some 13 600 L every day. The fuel for the generators, and also for cruise ships and automobiles, arrives by oil tanker from mainland Ecuador. Over the past decade, the number of tankers coming to the islands has jumped from a few per year to a few per month now. For years, conservation experts dreaded an oil spill. On 16 January 2001, it happened.

That night, the Ecuadorian tanker Jessica took a wrong turn near San Cristóbal’s harbor, rammed into a reef, and ran aground, leaking more than 500 000 L of diesel and bunker fuel. The spill dirtied sea lions and tortoises and killed a handful of pelicans and seagulls. Only a sudden change in ocean currents, which washed the oil out to sea, prevented the spill from becoming an even bigger ecological disaster.

The incident served as a wake-up call. Not long after, the Ecuadorian government decided to invest in renewable energy for the archipelago, and it teamed up with the United Nations Development Programme and the e8—an international consortium of electricity companies that supports energy projects in the developing world—to launch the US $10.8 million San Cristóbal Wind Project.

The goal of the project is to build a 2.4-megawatt wind system that will supply 52 percent of San Cristóbal’s annual electricity needs, on average. It might not seem like much, but that means reducing the amount of diesel burned by 950 000 L and preventing 3000 metric tons of carbon dioxide from being dumped into the atmosphere every year. “More important, it should reduce the number of tankers coming to the island,” Vintimilla says, “and so, the risks of another spill.”

I’M INSIDE WIND TURBINE NO. 1, ascending a narrow ladder that stretches upward for 50 meters. Inside this giant white-walled tube, with the fluorescent lights flickering, I almost forget I’m in the Galápagos. It’s more like being in a spaceship.

Looking up, I see a pair of legs belonging to José Moscoso, the site’s operations manager; below me is Tolan. At the top of the ladder, we unhook our safety harnesses and squeeze through an opening to get inside the nacelle, the turbine’s uppermost structure, which houses the generator and holds the blades. Powerful motors can rotate the nacelle so that the blades always face the wind. Made of fiberglass and polyester resin, the 29.5-meter-long blades sweep an area of 2700 square meters in a single rotation, the equivalent of six basketball courts.

The three blades spin at relatively low speeds of up to 25 revolutions per minute. A gearbox ups that rotation to between 750 rpm and 1650 rpm, to drive the 800-kilowatt generator, the heart of the machine. “That’s what makes everything possible,” Tolan says, pointing to a massive piece of steel and iron the size of a Volkswagen Beetle. “The flow of air becomes the flow of electrons.”

The generator produces alternating current whose frequency depends on how fast the wind is blowing and turning the blades, he explains. The electricity then flows into a cable that runs down the tower. Near the bottom, a rectifier converts the ac to dc, which then goes into an inverter for conversion back to ac at the desired frequency of 60 hertz. Finally, a transformer boosts the voltage to 13.8 kilovolts.

Moscoso opens a small hatch in the ceiling of the nacelle and takes a peek outside. How’s the view? “Está toda nublada,” he says. “It’s all cloudy.” Tolan tells me that on a clear day you can see almost the entire island and the deep blue Pacific all around. “It’s a million-dollar view,” he says. “To the south, there’s nothing but ocean from here to Antarctica.”

AS WE LEAVE El Tropezón, Tolan recalls how he first got involved with the project. He’d been working as a project manager at Industry & Energy Associates, a consulting firm in Portland, Maine. In 2001, Paul Loeffelman, director of environmental public policy at American Electric Power, the e8 member company chosen to lead the San Cristóbal project, called him up. Would he be interested in building a cutting-edge wind farm on a tiny island located 1000 kilometers out at sea, where 85 percent of the land consists of protected national park? Sure, replied Tolan, always up for a challenge.

To navigate Ecuadorian laws and energy policies, Loeffelman picked Vintimilla, a former director of Ecuador’s energy regulation agency. Tolan, a 47-year-old detail-oriented, straight-talking New York City native who graduated from the U.S. Merchant Marine Academy in Kings Point, N.Y., and Vintimilla, a 60-year-old mild-mannered engineer widely respected in Ecuador, made a formidable team.

Vintimilla’s first major task was persuading the government to establish regulations for wind-power projects, as San Cristóbal’s would be the country’s first. Then there was the issue of ownership. The plan was that the e8 would establish a trust entity to manage the project and gradually transfer control to Elecgalápagos, the local electrical utility. “We had to do so many reports for so many different people,” Vintimilla says.

In the meantime, Tolan pored over the engineering and financing details. A 2001 study had estimated that a wind system capable of reducing diesel generation by 98 percent would cost $5.4 million. To Tolan, those numbers looked far too optimistic. What’s more, since that initial study, annual electricity demand on San Cristóbal had grown from 4950 megawatt-hours in 1999 to 7150 MWh in 2006. Tolan recalculated the project’s cost—this time factoring in such details as how many construction cranes you’d need to rent and how much you’d spend relocating Miconia plants from the site--and concluded that the project would achieve a diesel reduction of about 50 percent at a cost of some $10 million.

“Everyone was asking me, ‘Jim, what did you do?!’ ” Tolan recalls. He had to explain that the typical costs for a big wind project in the United States—$1000 to $1500 per kilowatt—didn’t apply to the Galápagos, where transportation and environmental-related expenses brought the cost per kilowatt to $3500.

Tolan and Vintimilla also had to address concerns from the local community. Wouldn’t the turbines disfigure the pristine landscape and hurt tourism? The project managers convinced local leaders that the visual impact would be minor, because the towers wouldn’t be visible from town. Moreover, they argued, the idea of renewable energy in the Galápagos would appeal to environmentally conscious visitors, who might even want to go see the towering turbines.

IT TOOK FIVE YEARS for all the pieces—feasibility studies, business and financing plans, environmental licenses, and power-generating permits—to come together, but in September 2006 construction finally commenced. After a groundbreaking ceremony attended by project stakeholders and San Cristóbal’s mayor and bishop, Tolan ordered the wind turbines from Madrid-based Made Tecnologías Renovables and told Santos CMI, an Ecuadorian contractor, to start construction at the wind site, which is in a cattle-grazing area outside the national park.

First, though, a pier in San Cristóbal harbor got a 10-meter extension so that it could receive the 5000-metric-ton barges that would transport the wind turbines and construction equipment. The first barge delivered three concrete mixer trucks and a million kilograms of cement, and workers began building the towers’ massive foundations.

Tolan planned the schedule so that construction happened early in the year and not during the garúa season. But he couldn’t anticipate everything. On vacation in Quebec City in April 2007, he was awakened at 3 in the morning by a phone call: the ship sent to the port of Ferrol, in Spain, to retrieve the wind turbines wasn’t big enough to accommodate the 30-metric-ton nacelles below deck. Would it be okay to put them above deck, subjecting them to the salty weather of a North Atlantic crossing? Tolan said no. He wanted another ship.

The transportation delay added to a further delay at Ecuadorian customs, but in July 2007 a second barge finally arrived in San Cristóbal with the three turbines and five cranes to install them. Getting all that to El Tropezón was a dramatic operation, with 30-wheel trucks slowly parading through town, the gigantic turbine parts strapped to their backs. Workers ran just in front of the trucks, lifting up low-hanging wires with sticks, clearing people from sidewalks, and even temporarily moving a stone monument that stood in the way.

For the final phase of construction—erecting the 51.5-meter towers—two tubular pieces plus the nacelle were lifted into place by a 400-metric-ton Mantiwac crane, whose own assembly required two smaller cranes. With El Tropezón covered in thick fog, workers radioed careful instructions to the crane operator, who after many hours succeeded in positioning the turbine parts precisely, so that all the bolts lined up. By August 2007, the three turbines had been erected.

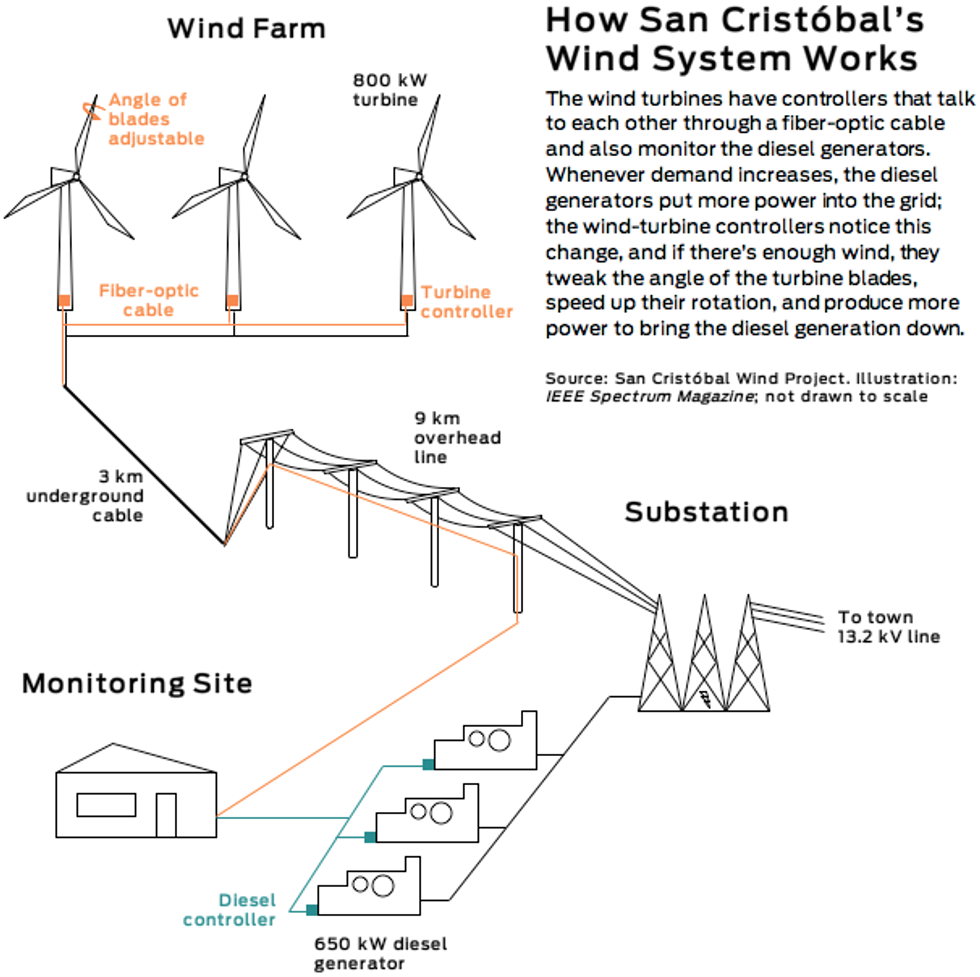

The San Cristóbal system is a wind-diesel hybrid. The electricity generated by the wind turbines and by three diesel generators converges at this substation before being transmitted to town.

The wind energy arrives at the substation through a 12-km-long transmission line. The 20-year old Caterpillar 650-kW diesel generators are located on-site, inside a concrete metal-roofed building. Exhaust stacks belch their sulfurous fumes into the air, and you have to wear earmuffs because the engines are so loud.

Though smelly, noisy, and polluting, the diesel generation is reliable. Outages happen only sporadically. Still, why not replace the diesel system entirely with wind power? The problem here as elsewhere is that the supply of wind varies quite a bit. When it’s very windy, Tolan says, 80 percent of the grid energy might come from wind. ”But when there’s almost no wind, we might put in very little—or nothing.”

That’s why San Cristóbal needs to keep the diesel generators running. The diesel system works as a reference, maintaining the voltage and frequency across the grid. And when there’s enough wind, the turbines can reduce the diesel generation to 25 percent of its maximum capacity—sometimes one or two diesel generators can even be shut down.

The Galápagos system differs from conventional wind-diesel hybrids in its use of an innovative control scheme developed by Made. In most conventional hybrids—in places like Alaska, Australia, and Vietnam—the wind turbines are always producing as much power as they can. If generation surpasses demand, excess power is stored in batteries; conversely, if wind speeds drop too much and generation falls below demand, the system turns to backup batteries.

The Galápagos hybrid doesn’t use auxiliary batteries, which are costly and add complexity to the system. Instead, the turbines automatically reduce or increase their power output according to demand. They do this by adjusting the angle of their blades. At the point where it attaches to the central hub, each blade can rotate, powered by a hydraulic actuator, by small angles up to 90 degrees. The rotation changes the way the blade’s surface is exposed to the wind and thus controls the turbine’s overall rotational speed. Each turbine has its own PLC, or programmable logic controller. The PLCs talk to each other through a fiber-optic cable and also monitor the diesel system. If lots of people turn on their air conditioners, for instance, the diesel generators put more power into the grid. The PLCs notice this change, and if there’s enough wind, tweak the angle of the turbine blades, speed up their generators, and produce more power to bring the diesel generation back down.

“The three turbines monitor each other and coordinate their power outputs,” says Carrión Pérez. “All the three brains talk to each other, but there’s no central brain.”

On the computer screen, he and his colleagues are fine-tuning the control algorithms to make the turbines’ increases and decreases in power output as smooth as possible. The task should take another week or so, and then the turbines can go into commercial operation—and the Spanish will get some downtime.

On San Cristóbal, Darwin encountered for the first time the archipelago’s most famous inhabitants, the giant tortoises. “These huge reptiles, surrounded by the black lava, the leafless shrubs and large cacti, seemed to my fancy like some antediluvian animals,” he remarked. Darwin went on to find much more as he explored the other islands during his five-week tour, including 13 types of finch with a “perfect gradation in the size of the beaks,” each adapted to a diet of plants, fruits, or insects—the clues for his breakthrough theory scattered before his eyes.

With the high-noon sun beating down, Tolan and I set out to retrace Darwin’s first steps on San Cristóbal. The spot where the naturalist is believed to have gone ashore is a tiny bay on the southwestern part of the island. Tolan warns me to beware of the massive, dark-furred male sea lions, which charge if you get too near. I tell him I’m more worried about the marine iguanas, the sharp-toothed reptiles that look like miniature dragons ready to take a bite out of your foot. “Nah,” Tolan says, “they’re vegetarians.”

For an engineer, Tolan has had to learn quite a bit about Galápagos wildlife. Take the Galápagos petrel. Tolan gets just as excited talking about this gray-and-white seabird as he does about power inverters. The petrel nests in shallow burrows in the humid highlands of San Cristóbal and other islands and is one of the archipelago’s many endangered animals. Invasive species like rats and cats eat petrel chicks, and cattle destroy their nests. In the last 60 years, the petrel population declined 80 percent.

Studies have shown that wind turbines and transmission lines can kill birds, although there’s no agreement on whether the number of dead birds is significant compared with the number of birds killed by other causes such as high-rise buildings and house cats. But in the case of an endangered bird, even a few dead ones are too many. So Tolan convened the Petrel Committee, composed of bird experts from local and foreign organizations, to investigate whether the Galápagos turbines would make the petrel’s life even more difficult.

The committee ruled out two potential sites for the turbines because petrels liked to nest in those spots. The group zeroed in on El Tropezón after it found no active nests. But they also had to make sure that petrels didn’t fly through the area. The birds are tricky to monitor because they stay out at sea, hunting for food during the day, and returning home only after sunset to feed their chicks.

So the committee dispatched a team of graduate students, equipped with night-vision goggles and microphones. The students hunkered down on El Tropezón and spent their nights looking and listening for petrels. After six months, they concluded that few birds flew where the towers were to be installed.

As we return to town at sunset, Tolan and I meet Francisco Cruz at the Calypso, a colorful bar and restaurant on the promenade off Charles Darwin Avenue. Tolan has hired Cruz, a bird expert who used to work at the Charles Darwin Foundation, to continue to monitor the site. Cruz is also one of the owners of the bar, a business he started with money he earned through his bird work. He calls the investment “petrel dollars.”

As we munch on a plate of patacones—fried mashed plantains—and sip Pilsener beer, Cruz reports that he and his assistants have found one dead bird. “Not a petrel—something smaller,” he says. “It appears it was dead before the turbines were built.”

Tolan says the Petrel Committee wasn’t just aiming to avoid killing birds; it also saw an opportunity to improve their chances of survival. Profits from the wind project are financing a 20-year program to try to keep rats, cattle, and cats out of the nesting areas. Saving the petrel has involved “a lot of work and resources and money,” Tolan says. “But, hey, anything for the birds.”

Three wind turbines will not in themselves solve such problems. Experts say the islands need a better socioeconomic model that makes the local communities part of the conservation process. The United Nations and the Ecuadorian government are both investigating ways to do that, including limiting the number of tourists without hurting the economy. But in terms of reducing the archipelago’s and the country’s reliance on fossil fuels, renewable energy will play an ever more important role.

“Any measure that we take to diminish the amount of oil circulating between the islands or from the continent to the islands is a good measure,” says Cecilia Falconí, an officer at the United Nations Development Programme in Quito. “It’s not the size [of the project that matters], but the example. San Cristóbal is the first wind project in all of Ecuador. This is a lesson that all the country will benefit from.”

With their work on San Cristóbal nearly completed, Tolan and Vintimilla are already envisioning the next steps. Their idea is to find ways of using the excess wind power the turbines could produce at night, when grid demand is lower. One way to harness that energy is to use special refrigerators that make ice at night and use no energy during the day. Another possibility is to introduce electric scooters and electric cars whose batteries could be charged at night.

But these are plans for the future. Today, sitting on the balcony of the Miconia Hotel overlooking the island’s harbor as the barks of sea lions echo in the background, Tolan and Vintimilla prefer to reminisce about what it took to make the project happen. “In 2004, we installed the first wind-metering tower, and I felt something was starting to happen,” Vintimilla says. “Now, when I see the spinning of the blades, it’s a big emotion.”

To Probe Further

For more information on the San Cristóbal Wind Project, including a full report describing its objectives, benefits, and technical and financial information, visit the project Web site.

The San Cristóbal Wind Project was led by American Electric Power, one of the largest U.S. electric utilities and a member of the e8, an international consortium of energy companies that supports sustainable energy projects in developing nations. To learn about other e8-backed projects, visit the consortium’s Web site.

The wind project managers carefully chose the location of the turbines to avoid disturbing the endangered Galápagos storm petrel, which lives in the highlands of San Cristóbal. More information about the bird and what the project managers did to protect it is described on the San Cristóbal Wind Project’s Web site.

To learn more about visiting the Galápagos Islands—how to get there, where to stay, and when to go—see the tourist information sections on the Web sites of the Galápagos National Institute and the Galápagos Conservation Trust.

Charles Darwin visited the Galápagos archipelago in 1835 during a five-year expedition to several places around the world. His journal describing that trip—which he called “by far the most important event in my life”—was first published in 1839 and is now known as The Voyage of the Beagle. You can read the entire book online at Google Book Search.

- Can This DIY Rocket Program Send an Astronaut to Space? ›

- This Axial-Flux Motor With a PCB Stator Is Ripe for an Electrified World ›

- Are Vertical Axis Turbines the Future of Offshore Wind Power? ›

- Software Turns Promise Up for Offshore Wind - IEEE Spectrum ›