Virgin Oceanic’s Voyage to the Bottom of the Sea

Virgin Oceanic hopes to launch a new era of manned deep-sea exploration

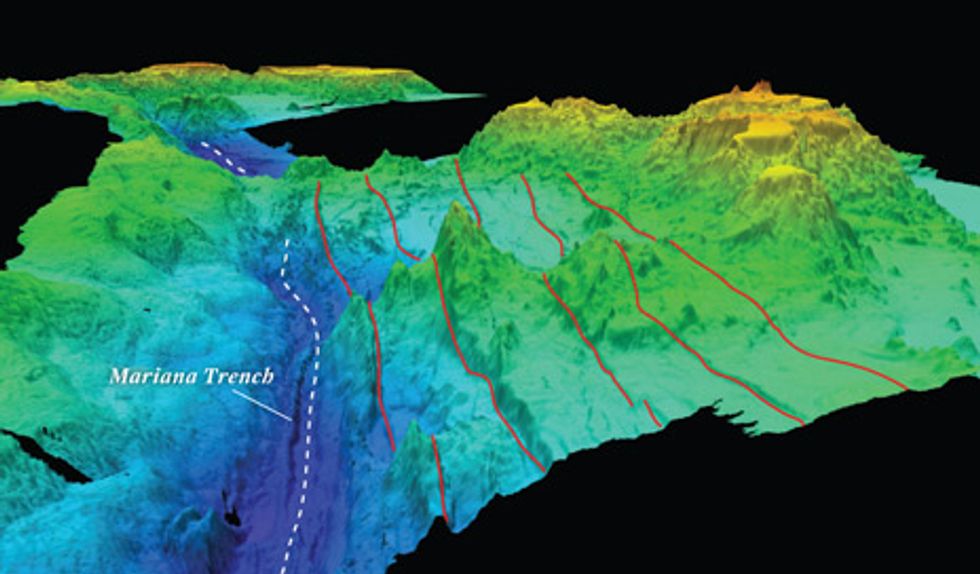

As the battered little boat slides down a 3-meter ocean swell into the next trough, Chris Welsh grits his teeth and peers out into the storm. Sheets of rain pummel the dark windows of the bridge, and a Micronesian sailor wrestles with the wheel. It’s past midnight on a July night and we’re bobbing over the almost 11 kilometers of water that fill the deepest abyss on Earth, the Mariana Trench. Welsh is leading a small party of engineers, scientists, and adventurers under the banner of Virgin Oceanic; they’ve chugged out here aboard a 20-year-old ferryboat to test some unmanned deep-diving probes. It’s the first step in what they hope will be a glorious high-tech adventure, in which a man—Welsh, specifically—will visit the bottom of the trench before the end of this year.

But right now, most of us would be happy just to make it back to Guam, 130 km (81 miles) to the north. Another wave breaks over the boat and crashes down on the cabin house, dousing the upper deck. I recall a plaque mounted on a table in the main cabin that admonishes, “No passengers more than 20 miles from shore.” This 20-meter-long vessel is what oceanographers call a “ship of opportunity,” which means it was pressed into service for the mission basically because it was available. Welsh turns to the captain, who lives in the Mariana Islands, and asks, “In your experience, what usually happens in a storm like this? Does it get better? Does it get worse?”

The captain keeps the boat’s prow pointed firmly into the waves. “I don’t know,” he says. “I’ve never seen it like this.” It occurs to me that if the boat sinks, it will take 3 hours to reach the seafloor.

Of course, it wouldn’t be real adventure if there wasn’t any danger. Like the South Pole, the peak of Mount Everest, and the moon, the Mariana Trench is a singular place that looms large in the human psyche. Countless ordinary people have imagined what it would be like to be there, and a very few extraordinary people have actually managed to go. Of all those singular places, the bottom of the Mariana Trench has had the fewest visitors—precisely two. In 1960, U.S. Navy lieutenant Don Walsh and Swiss engineer Jacques Piccard rode down in a primitive vehicle called a bathyscaphe (essentially a small metal sphere attached to an enormous bag of buoyant gasoline). No one has been there since, although three unmanned vehicles took the plunge in the 1990s and 2000s.

If Walsh and Piccard’s bathyscaphe was a dirigible, the sleek experimental vehicle being built for Welsh is a fighter jet. Welsh plans to pilot it on the world’s first solo dive to the trench bottom. He’ll be accompanied by an entourage of robotic landers, the prototype of which we’re now testing in this stormy sea. We dropped the lander 6 hours ago, and by now it has completed its round trip to the seafloor and is bobbing somewhere out there on the dark waves. The researchers on board dearly want it back, with its payload of deep-sea water samples. But the radio beacon attached to the probe isn’t sending out its location signal, and there’s no sign of the instrument’s flashing strobe light in the storm. If an unmanned probe carrying only electronics can run into this much trouble in the Mariana Trench, what difficulties will confront the actual sub, with its cargo of human life?

Welsh doesn’t seem too worried. He’s a firm believer in calculated risk; he does the math and then forges ahead. “I think one of the stupidest phrases in the English language is ‘He died doing what he loved,’ ” Welsh told me before we set out from Guam. He’s figured out the possible health consequences of drinking eight Diet Cokes a day and found them acceptable. He flies planes and helicopters and sails racing boats because he trusts his abilities and finds the rush to be well worth the risk. And he has no intention of dying on a crummy old ferryboat bobbing on the surface of the Pacific—or in the sub that will take him to the nadir of the world.

Welsh previously got his thrills with sports cars, planes, and sailboats, but around 2010 he started toying with the idea of setting some kind of world record. He wasn’t too particular—the fact that he’d never parachuted didn’t deter him from thinking about attempting the highest-altitude skydive. Then, while inquiring about Fossett’s up-for-sale yacht, he learned that the boat had been modified to launch a sub from its deck and that the sub was also for sale. He’d never piloted a submersible before either, but once he saw the sub he was hooked. “Buying the sub was enormously consistent with my past history,” Welsh declares. “Each aircraft that I bought, I wasn’t licensed or qualified to fly when I bought it. But I learned.”

At around US $10 million, the Mariana expedition is beyond the capacities of the lower order of rich people. So Welsh, who made his pile in real estate, approached Sir Richard Branson, the chairman of Virgin Group and No. 4 on Forbes’s list of British billionaires. Branson founded Virgin Galactic, a company that plans to rocket wealthy tourists to the edge of space; an oceanic venture seemed like the perfect complement. Branson signed on, agreeing that Welsh would pilot the sub on the first Mariana Trench dive, while Branson will plunge the sub into another deep ocean trench.

Sending anything more complicated than a rock to the bottom of the trench, where the pressure is 1100 times as great as at sea level, is a momentous engineering challenge. Ever try to build a sleek hydrodynamic enclosure that can withstand a pressure that’s equivalent, over its entire surface, to the weight of four pickup trucks pressing on an area the size of a postage stamp? Didn’t think so.

Most governments long ago gave up on trying to send people to the bottom of the deepest ocean trenches, citing the challenges and the seeming pointlessness of the endeavor. After all, a sub like Japan’s Shinkai 6500, currently the deepest diving manned submersible, can reach 98 percent of the world’s seafloor, although it can’t make it even two-thirds of the way down into the Mariana Trench.

To probe deeper, down to the other 2 percent, engineers have built autonomous underwater vehicles (AUVs) and remotely operated vehicles (ROVs). Just as space explorers have come to rely on rovers and unmanned probes to survey our solar system, oceanographers have chosen robotic vehicles and ocean observatories to be their proxies in the deep. But for true believers like Welsh and the Virgin Oceanic team behind him, there’s nothing like having a human brain down there to see, experience, think, and improvise.

Welsh and Virgin aren’t the only private explorers in this race to the bottom. Decades after governments abandoned the deep, deep sea, a crop of entrepreneurs have taken up where the world’s research institutions left off. No fewer than four private companies are designing or building manned submersibles capable of reaching the lowest of the low. James Cameron, the director of blockbuster movies like Avatar and The Abyss, is financing the construction of a one-person vehicle that will likely be studded with cameras. Triton Submarines, located in Florida, has designed a sub that would bring three people down to the seafloor in an innovative glass pressure vessel, which would certainly give passengers a great view. Deep Ocean Exploration and Research, a California company with funding from former Google CEO Eric Schmidt, is also designing a three-person sub.

During the July expedition to the Mariana Trench, marine engineer Kevin Hardy [bottom] prepares the seafloor lander’s sample tubes. Researchers hope that water samples from more than 10 000 meters down will contain strange new life-forms. Once the lander begins its plunge [left], it takes 3 hours to reach the seafloor.

Top: Eliza Strickland; Bottom: Roxie J. Cirino

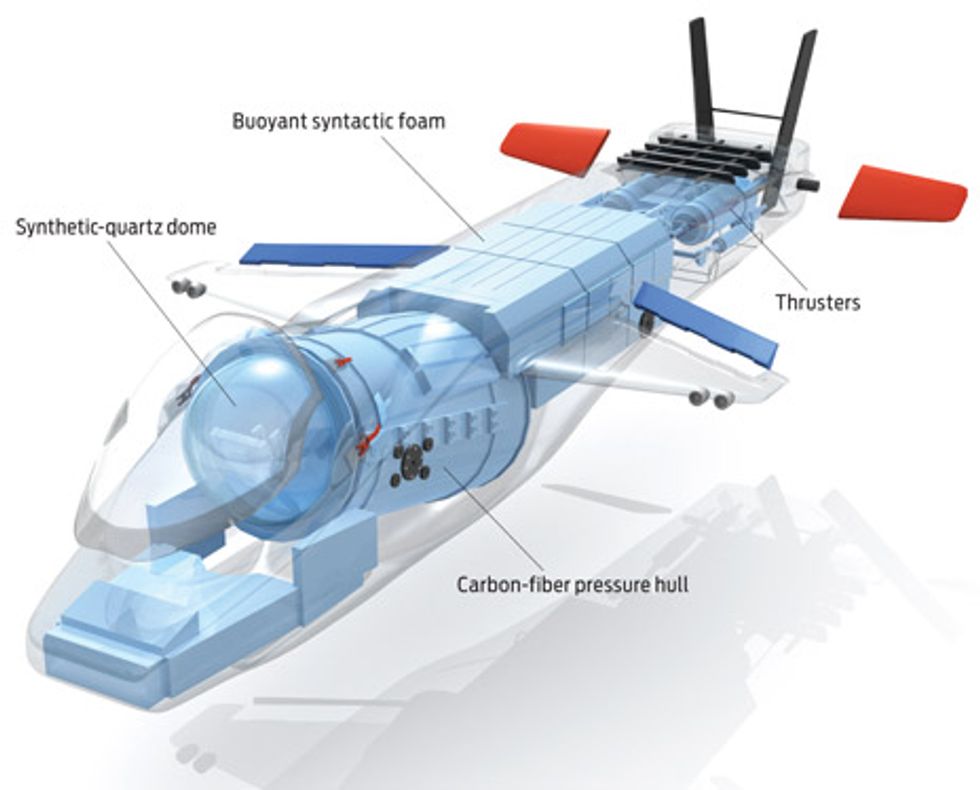

The sleek craft also breaks with the tradition of using a sphere—the most inherently pressure-resistant shape—for the crew capsule. Instead, the pilot will lie inside a cylindrical pressure hull made of carbon fiber. “It’s the strongest, lightest material we know on the planet,” says Hawkes, and it’s the main reason why the sub weighs only 3600 kilograms. A full-ocean-depth sub built around a steel sphere would weigh about 10 times as much, says Hawkes. The six manned deep-sea submersibles operated by government agencies around the world are so heavy that they require specially equipped and enormously expensive mother ships to launch them, while Hawkes’s sub is designed to be hauled atop, and launched from, any reasonably large boat.

The entrepreneurs now at the forefront of manned deep-ocean exploration don’t justify their projects in terms of benefits to science. Some, like Welsh, say they’d like to investigate the bizarre life-forms in the dark deeps and the geological forces that undergird the Earth’s mantle. But the motivations also have to do with thrills, ego, bragging rights, and the possibility of a financial return in the future. If all goes well with Virgin Oceanic’s solo sub, the company plans to build a two-seater to hold a tourist in addition to a pilot.

For Hawkes, though, the ultimate payoff would be if his lightweight, inexpensive craft leads the charge into a new era of exploration. “In my view, the existing manned submersibles are almost an extinct species,” says Hawkes. “You do need the wild, experimental craft to unlock the future, to show that it can be done. Unless we can break through to a different kind of manned craft that is dramatically different from existing vehicles, marine exploration in the future won’t be manned—it just won’t be economically feasible. It will all be done with robots, and we won’t have access to our own planet.”

For the past few days we’ve been nervously tracking Tropical Depression 11, a nasty squall south of Guam. Around midnight, just when the lander is supposed to bob to the surface, the storm finds us. “Visibility just went from across the universe to 10 feet,” says Kevin Hardy, the marine engineer who designed and built the lander.

We had dropped the seafloor lander over the side of the boat around sunset, sending it down into a patch of the Mariana Trench called the Sirena Deep, which at about 10 640 meters is not quite as deep as the trench’s absolute bottom, the 10 994-meter Challenger Deep. Hardy had watched fondly as its cheerful orange flag disappeared beneath the waves and kept tabs on its descent with a sonar communication system. When the probe finally reached the bottom, he transmitted an acoustic command that sent electricity through a “burn wire” to disconnect the anchor (a 50-kg engine block picked up in a Guam junkyard), and he started tracking his lander all the way up through kilometers of black water. On the surface, however, the swells were getting rough, pushed to greater heights by the strengthening wind. In the Pacific night sky, the dazzling glory of the Milky Way began to disappear behind ominous clouds.

The heart of the lander is a hollow glass sphere that protects the electronics and provides buoyancy; that sphere is encased in sturdy orange plastic. Below that is a second sphere for additional buoyancy, and then two long sample tubes to collect water and tiny organisms from the bottom of the trench. The scientists on board are particularly interested in any piezophiles—pressure-loving critters—that may live in the Sirena Deep.

When the storm winds begin to rage, Hardy asks Welsh to come up to the bridge to consult on the status of the mission. The two men struggle across the rain-lashed deck as the boat pitches and lurches. Lightning bleaches the sky, illuminating the two pathetic life rafts with mesh-net bottoms. Hardy scans the dark waves, but there’s no sign of the lander’s strobe. A lightning strike may have fried the lander’s electronics, he tells Welsh. Improbable though it may be, such a strike would also explain why the lander’s radio beacon isn’t working either—the radio receiver hasn’t picked up a single chirp. Without those two systems, the lander is gone for good, unless somebody just happens to spot the little orange globe out there in 10 or 20 square kilometers of storm-tossed Pacific.

Under sunnier skies, on the shore of San Francisco Bay, I paid a visit to Hawkes’s marina workshop, where the sub sat in a dozen pieces inside a small storage unit. The wings were stacked to one side, oxygen canisters for the life-support system were boxed up in the front, and the thick steel plates that form the sub’s ballast lay on the floor. Jay Tustin, the lanky and unflappable technician who’s overseeing the sub’s preparations for the Mariana Trench, surveyed the pressure hull, a black cylinder with 13-centimeter-thick walls, and said, “We just don’t know how happy it’s going to be at full-ocean depth. It’s the big unknown.”

To survive the dive into the highest pressure environment on Earth, the sub is relying on an exotic material with exciting but untested capabilities. The carbon fiber material that forms the hull is some of the toughest stuff on Earth, but it’s never been used in quite this way before. The carbon fibers, which are wound around an epoxy matrix, are fantastically strong in tension when the pressure is applied from inside. But when external pressure causes compression, the material doesn’t have quite the same strength.

Tustin noted that the original owner of the sub, the late Steve Fossett, was “very much an adventurer, very much used to taking risks.” Tustin explained that with human-occupied vehicles, Hawkes’s team typically designs with a 2-to-1 safety factor; in this case, that would mean designing a hull that could withstand the pressure at the purely hypothetical ocean depths of 21.8 km. “We got this to a 1.4 safety factor, and we wanted to do more testing, but Steve cut it off,” said Tustin. I asked Tustin if Welsh was comfortable with the 1.4 safety factor. “He’s pushing ahead,” Tustin replied. “I think that tells you all you need to know.”

The bulk of the sub—the cylindrical pressure hull and the fuselage around it—was intact, and Tustin invited me to clamber in. The glass dome attached to the front of the pressure hull swung open with a resonant creak, allowing me to slide in feet first. Inside the hull, I lay on my stomach in a modified Superman-in-flight pose, propped up on my elbows so I could grip the two joysticks that control both the thrust and the plane-type parts that allow the pilot to steer: ailerons in the wings and elevators and rudders in the tail. With a combination of the hydrodynamic forces and about 270 kg of ballast, Tustin says the sub will get to the bottom of the Mariana Trench in 2 hours, leaving plenty of battery time for an exploration of the seafloor.

Tustin and other members of Hawkes’s team began building the sub in 2005. The time was right to go for full-ocean depth, Tustin says. The team used light and powerful lithium-ion batteries developed by the auto industry for electric cars. The back half of the sub holds blocks of a buoyant material called syntactic foam, composed of hollow glass microspheres embedded in an epoxy matrix; the newest type of this material can stand up to the deepest sea pressures. Once the sub drops its ballast, that buoyant foam will bring the pilot home.

The acoustic communication system isn’t finalized yet—Virgin Oceanic’s current system works only to depths of about 5 km. The company’s engineers are looking for a replacement system, but Tustin says that during Welsh’s dive, he shouldn’t count on advice from the surface. “My feeling about it is that once Chris gets down there he’s on his own,” Tustin said. “It’s the dark side of the moon.”

The pilot’s head will be within the pressure-resistant transparent dome on the front of the pressure hull. This will give him a much better view than researchers get in government subs, which sport just a couple of small portholes. The original plan was to use high-strength glass for this component, but when the glass dome was tested in a pressure chamber, it cracked under the pressure it would experience at just 5000 meters. The thick glass is now fissured all around the edges where it meets a titanium ring.

In the trench, such cracks wouldn’t be just a disappointment, they’d be deadly. So Virgin Oceanic hired a company to make a new dome out of a 1270-kg ingot of synthetic quartz. Then a company that makes lenses for NASA telescopes spent one year hollowing it out into a hemispherical shape. This new dome will be tested in a pressure chamber at Pennsylvania State University this spring.

I’ve never been as happy to see daybreak as I am the morning after the storm, with our ferry pushing through thick fog over a gray sea. On the bridge, Welsh and Hardy scan the horizon, looking for the little orange flag atop the lander’s orange spheres that would signal unlikely victory. “We’re mowing the ocean,” said Hardy as the captain steers us through a slow search pattern around the site where we dropped the lander. But even if the lander survived the storm, it had all night to drift away.

The radar shows an even bigger patch of storm barreling toward us from the south, and the harbor authorities in Guam are advising all ships to head back to port. “The storm is moving at about 13 knots. Our boat travels at 10,” Hardy tells us, and there is nothing to do but abandon the search and motor back to Guam. Hardy insists that the mission hasn’t been a failure, though. He likens his lost lander to the earliest moon missions, when the Soviet Union sent probes crashing into the lunar surface. “We learned a lot,” says Hardy, “but we didn’t get the craft back.”

So we flee before the storm, which will turn into Super Typhoon Muifa over the following days, and we kiss the $30 000 lander good-bye. But that’s the price you pay for trying to explore the mysterious deep—sometimes the deep claims your emissaries. Standing on the bridge, staring into the empty gray sea, Welsh vows to press on. “We’ll do it better next time. We’ll build four more. We’ve just got to learn how to overcome the obstacles, and we will.”

This year, while Hardy builds new and improved landers, Welsh will oversee tests of the sub’s pressure hull and its new quartz dome. If all that goes well, before the end of this year the team will be back out here over the trench, attempting a much more ambitious mission with much higher stakes. Welsh says that when he pilots the sub on its long, long dive into the Mariana Trench, he’ll be thinking about the pressure, of course, and trying not to dwell on the fact that any weakness in the hull means implosion and instant death.

“I don’t have the appetite for roulette,” he says, “but there is a need for gumption in science and exploration.” Virgin Oceanic is bringing the gumption back.

This article originally appeared in print as “Voyage to the Bottom of the Sea.”