Elsewhere in this issue, we feature 10 engineers who are doing some very cool work [see "Dream Jobs 2004"]. Many of these folks started off studying and working in a traditional engineering discipline before landing in their chosen careers. Increasingly, though, engineering schools are offering specialized programs that aim to give students a head start down these less traveled roads of engineering.

This month, we look at engineering programs that are teaching the technology of creating entertainment. Their rationale is obvious: popular amusements and hobbies, from movies to computer games to sports events, are becoming more and more technologically sophisticated, and they demand new generations of engineers who know how to build them. Then, too, the prospect of dreaming up new ways for people to have fun appeals to many students; at a time when engineering enrollments are flagging, such programs help draw students in.

The newly created Entertainment Engineering and Technology program at the University of Nevada, Las Vegas (UNLV), for example, is looking at how to engineer theme parks, theatrical productions, sports events, and other large-scale entertainment. Another program, at the DigiPen Institute of Technology in Redmond, Wash., is entirely devoted to teaching computer game making and animation. Of course, they're not the only ones mining this popular and lucrative vein; for a list of other schools that offer degrees in some aspect of entertainment engineering, see " Entertainment and Engineering: Where to Study."

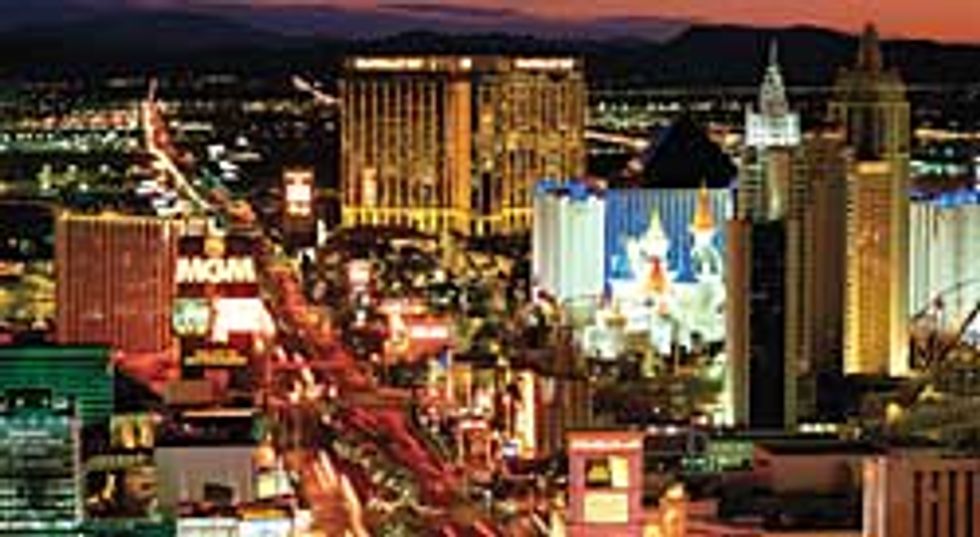

Engineering "The Strip"

From pyrotechnics to virtual reality, the biggest shows in Las Vegas rely on engineers. UNLV's Entertainment Engineering and Technology program is teaching engineering students how to apply their imagination, as well as their technical know-how, to designing these lavish spectacles.

One purpose of the program, says Darrell W. Pepper, dean of UNLV's engineering school (currently on leave as a Congressional Fellow in Washington, D.C.), is to help students find their way into this kind of "dream career." Another goal, he says, is to "develop state-of-the-art entertainment design, assisting with the introduction and improvement of innovative technology into [a company's] mainstream operations through partnerships and collaborations."

The program, developed jointly by the colleges of engineering and fine arts, thus stresses an interdisciplinary approach. The curriculum ranges from mechanical and civil engineering to art and architecture, with faculty drawn from engineering, arts, business, and hotel administration. Also on hand to help design courses is Entertainment Engineering Inc., in Burbank, Calif., which has produced a number of shows and rides in Vegas.

The demand is high for such expertise, Pepper says. "Entertainment is escalating upward in technological sophistication. Look at the movies now being made, as well as the PC games, theme rides, and rock concerts." In total, it's a multibillion-dollar industry.

In the theme park business, for example, there's fierce competition among companies like Universal Studios, Six Flags, and Disney to see who can design the coolest, most technologically sophisticated rides. In Las Vegas, too, elaborate rides and theatrical productions are found in hotels around town, from the Pirate Ship show at the Treasure Island hotel to the Star Trek Experience at the Las Vegas Hilton. To date, much of the development of the Vegas installations has been done by companies outside Nevada. The idea of incubating some home-grown talent helped spark the UNLV program.

Since 2001, students have been able to pursue the Entertainment Engineering coursework to fulfill a minor degree; starting next fall, an undergraduate degree will be offered. The construction technologies courses, for example, focus on creating the high-tech facilities that can support Vegas-style productions. An engineering student might study advanced materials that could be used in such productions. Robotics and animatronics, used to bring many Vegas shows' characters to life, are another area of study.

Students get a taste of entrepreneurship through the E-Club, a campus group that seeks to exploit the commercial potential of the entertainment engineers' senior design projects. Time is also set aside for exploring the world beyond the show makers on the Vegas strip. At a recent community outreach event, entertainment engineering majors worked with high school seniors to design robotic dogs using the Lego Mindstorms Robotics Invention System.

Pepper expects graduates to have no problem finding jobs. "Every company that we've talked to...has basically said, 'If UNLV had students with experience in this field, we'd grab them in an instant.' "

Serious Play

With the video game industry bringing in more than US $10 billion per year, software development companies are racing to keep up with demand. That means they need talented programmers who have both the technical chops and the spark of video game aficionados.

At DigiPen Institute of Technology, game making is a way of life. Founded in 1988, DigiPen now offers degrees in real-time interactive simulation, computer engineering, and three-dimensional computer animation.

But be warned: it's not all fun and games. "The biggest misconception about DigiPen is that it is a game design school," says its chief operating officer, Jason Chu. "DigiPen's real-time interactive simulation program involves basic math and science topics, such as calculus, finite elements, differential equations, wavelets, data structures, artificial intelligence, and ray tracing." Beyond just technical skills, students also learn how to perform in teams, design projects, and produce on a schedule.

Situated in the leafy burg of Redmond, Wash., next door to Nintendo of America and down the street from Microsoft, DigiPen very much resembles what one might imagine a game university to be. Clusters of Mohawked and baggy-jeaned students hang outside playing Hacky Sack. A library bulges with back issues of gaming magazines. A lunchroom bleeps with the sounds of arcade machines.

During their first year, students learn the basics of writing a game design document--the industry bible for such a project--and create their own text-based and puzzle games. In subsequent years, they'll cover more sophisticated games--from the old Mario Brothers side-scrolling style to today's elaborate 3-D action games. By the time they graduate, student teams will have produced up to a half dozen games from concept to completion.

DigiPen rounds out the hard-core coding courses with a range of humanities classes. Even the most ardent programmers take English, art, and sociology. These courses, though, all bear the DigiPen imprint. A mythology class is spun as Mythology for Game Designers. ENG 400 means Creative Writing for Game Design.

DigiPen students have a high chance of landing a job in the industry. According to the school, nine out of 10 graduates obtain a game-related job.