Keeping Score in the IP Game

Quantity and concentration of patents strengthen the case for legislative reform

A U.S. federal jury in February ordered Microsoft to pay Alcatel-Lucent US $1.52 billion in damages for infringing its intellectual property in MP3, the ubiquitous music-encoding software. Although in August an appeals judge reversed the decision in part and canceled the damages, the new ruling did not address Microsoft's main complaint, namely that U.S. patent law encouraged the jury to put excessive value on the IP in question. Microsoft may ultimately obtain a settlement it considers completely fair, but that could take so many years of costly litigation that even if the company wins, it will have lost.

The Microsoft-Alcatel MP3 case is just one of many that suggest to some that the patent system itself has lurched out of control, giving too much power to those laying claim to intellectual property and allowing too much leeway to patents of dubious quality or worth. Surely the case that has most captured the public imagination was the dispute over the technology of the BlackBerry personal communicator—which went on for years between Research in Motion, of Waterloo, Ont., Canada and NTP, a patent holding company in McLean, Va. Finally, last year RIM paid NTP upward of $600 million, complying with a court judgment.

The BlackBerry case drew attention to another much-criticized effect of the U.S. patent system: the presence of “trolls,” who allegedly acquire patents, sit on them hoping that one or more will turn out to have crucial business applications, and then go to court to obtain what critics call extortionist payouts.

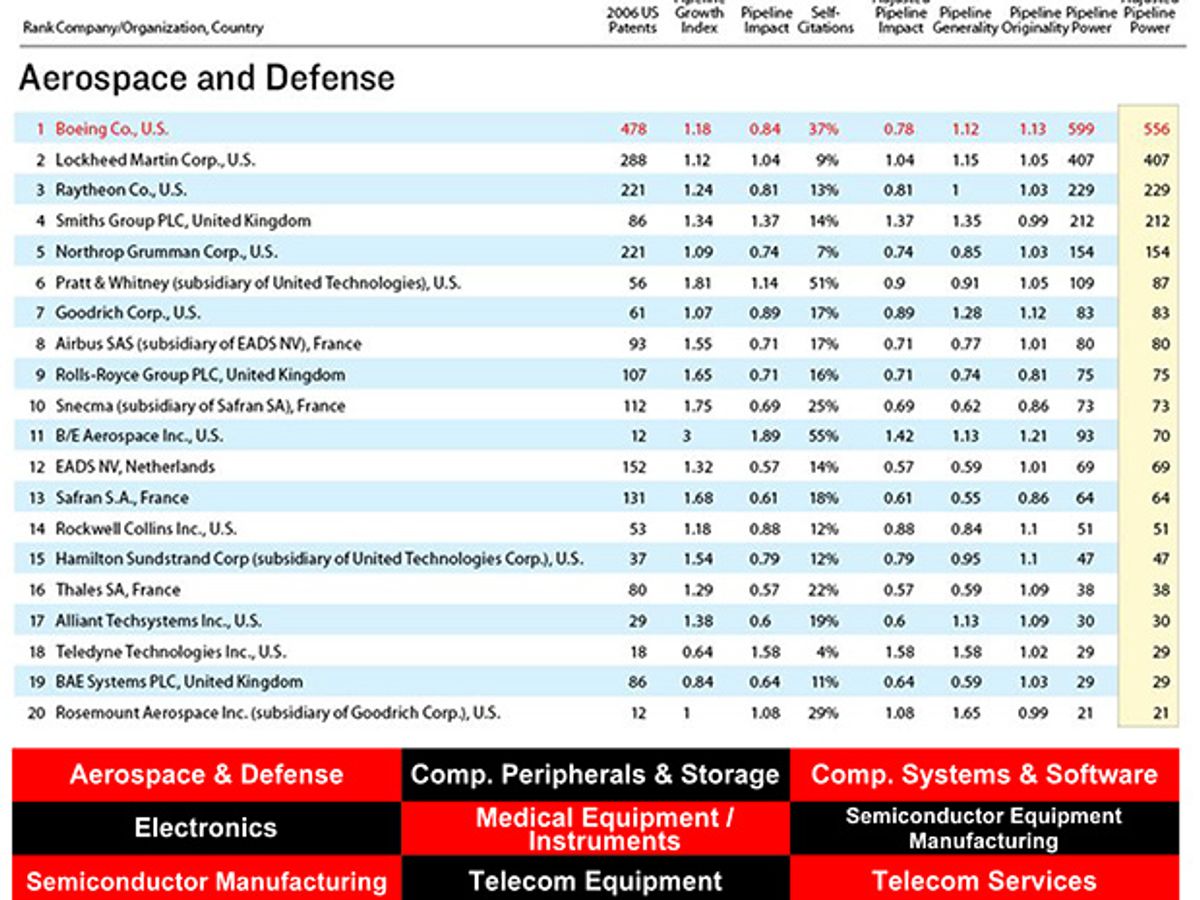

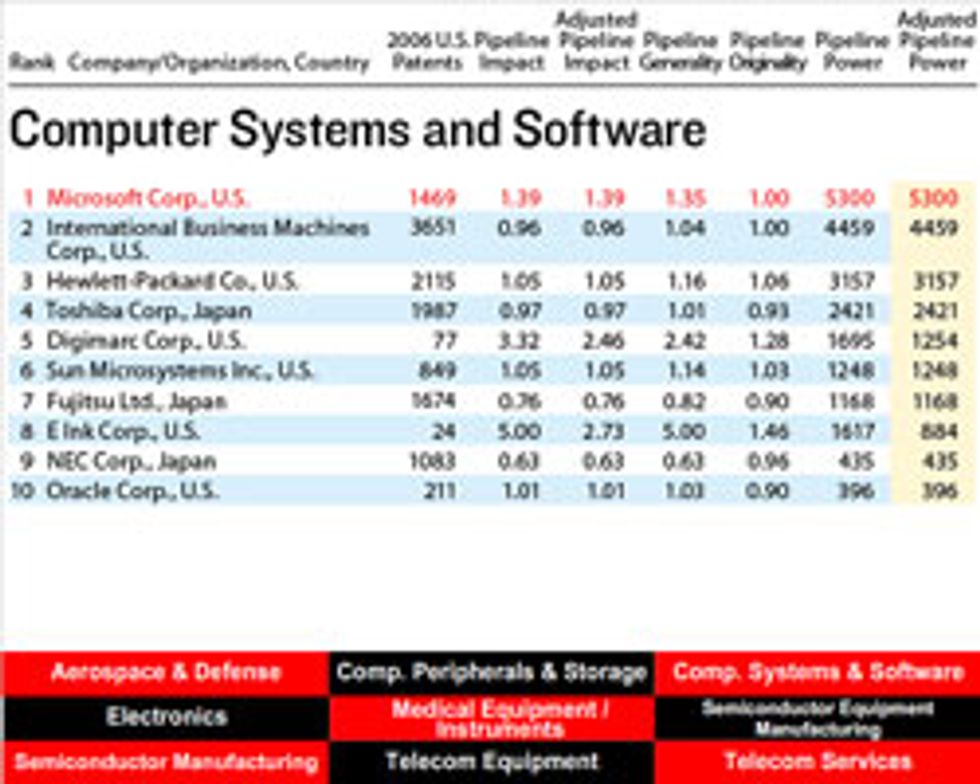

The data on U.S. patent awards for 2006 show that the patents in any given field still go to a few top companies, that there is little change from year to year among the dominant firms, and that big gaps yawn between the leaders and the runners-up. In almost all branches of electronics, computing, and telecommunications, awards made to the leading company jumped mightily from 2005 to 2006—by as much as 48 percent in semiconductor manufacturing, 60 percent in telecommunications equipment, and 65 percent in electronics [see table, "Patent Push"].

Steven J. Frank, a patent lawyer in Boston and author of the 2006 book Intellectual Property for Managers and Investors (Cambridge University Press), cautions that such studies of patent concentration and impact should be treated warily. “Just looking at the leaders, you have to ask what their game is,” Frank muses. “Are they just trying to look like IP dynamos? Are they engaged in a kind of land grab?”

Of course that goes, too, for smaller companies making big jumps in the ranks [for some examples, see table, "Patent Performers on the Move"],some of which might be emerging stars, while others might be merely padding their patent portfolios as a public relations exercise. To take the numbers at face value, however, and to judge from the fields in which the companies are shifting position most radically and frequently, computing, semiconductors, and telecommunications appear to be among the most dynamic areas in what the patent world broadly calls information technology (IT). Presumably, some chip and telecom companies are being truly innovative, while others may be acquiring patents mainly to defend themselves against possible litigation and position themselves to bargain effectively in cross-licensing arrangements.

IEEE Spectrum's compilation of patent awards and patent impact was prepared by 1790 Analytics, a Haddonfield, N.J., company that specializes in evaluating intellectual property. This is the second year that the firm, which takes its name from the year the first U.S. patent was awarded, has provided its data to us.

The methodology this year is essentially the same as last year's [see ”Patent Power,” Spectrum, November 2006 at /nov06/4699]. This year, however, 1790 added a measure to account for self-citation, which produces lower Pipeline Impact ratings for companies whose patents are referenced mainly internally.

Take Boeing as an example, suggests 1790's director of research, Anthony Breitzman: its raw Pipeline Impact value of 0.84 drops to 0.78 when adjusted for self-citation. Largely because of the self-citation penalty, Micron Technology, a semiconductor maker in Boise, Idaho, falls sharply from being last year's overall patent winner and is replaced at the top of the heap by Microsoft.

Looking at the compilation as a whole, the impression is more one of stability than of change. In almost every major subfield of IT, the same two or three companies appear among the top three or four. In fact, the top scorer changed in only one of the nine subfields: the newly merged Alcatel-Lucent overtook Motorola in Telecom Equipment.

The more things change, the more they stay the same, the French say…until, they might add, things really do change. This year, as this issue goes to press, Americans may at last see some real change in a patent system that almost every analyst considers seriously flawed. In fact, Congress is debating a reform bill that appears to have been developed in an intellectual and rational process, an event as happy as it is rare.

The reform proposal began to take shape about three years ago, when a unit of the National Academy of Sciences headed by Stephen A. Merrill produced a report called ”A Patent System for the 21st Century.” The report recommended creating a procedure for challenging patents after they are issued, bolstering the traditional standard that patents should be confined to ”nonobvious” ideas, and strengthening the overwhelmed U.S. Patent and Trademark Office. It also questioned U.S. rules that grant triple damages for ”willful” infringement and give priority to those who are the first to invent something over those inventors who are the first to file for a patent.

The result was the proposed Patent Reform Act of 2007, sponsored in the Senate by Patrick Leahy (D-Vt.) and Orrin Hatch (R-Utah) and in the House by Howard Berman (D-Calif.) and Lamar Smith (R-Texas). It would establish a procedure for challenging patents after their issuance, limit the ability of litigants to shop around for courts deemed sympathetic, redefine what constitutes willful infringement, and set damages based on the patent's contribution to a product's value, rather than on the product's total value (a policy known as balanced apportionment). This last point addresses the issue in the Microsoft MP3 case. Microsoft’s penalties were evidently set according to the total value of MP3 use involving its Windows Media Player.

Who will gain and who will lose if the bill becomes law? Basically, lobbying on the legislation has pitted the IT industries—including electronics, computing, and semiconductors—against the biomedical and pharmaceutical industries, which together account for most U.S. patents, says Frank.

Biomedical and pharmaceutical companies want ironclad patent protection, because they depend on a tiny handful of blockbusters to defray the billions of dollars they spend investigating hundreds of drug candidates that never pan out. Those blockbusters typically stand or fall on one or two patents. In IT, on the other hand, a winning product often results from a great many patents—MP3, Wi-Fi (IEEE 802.11), and 3G cellular telephony are excellent examples. Here, “things are less clear-cut” than with pharmaceuticals, Frank says, as it's less obvious that any particular patent is essential to accomplishing any particular thing. The big IT companies typically worry about being held liable by too many different parties for exorbitant damages.

Lobbyists include, on one side, the Business Software Alliance (composed of Microsoft, Apple, Hewlett-Packard, and a host of others) and on the other side, the Biotechnology Industry Organization and the Coalition for 21st-Century Patent Reform (representing, among others, drug maker Eli Lilly & Co. and consumer goods maker Proctor & Gamble). But even within the broad IT and pharmaceutical groupings, there are significant differences of opinion.

A survey last year of U.S. members of the IEEE found that they were not unanimous on the merits of the proposed bill. The IEEE’s volunteer-driven lobbying arm, IEEE-USA, has submitted critical opinions about the draft legislation, saying it wants a bill but a better bill.

Under the circumstances, it's more than a little remarkable that a bipartisan consensus has formed around a patent reform bill that largely captures the spirit of what the NAS and what other critics such as Adam B. Jaffe and Josh Lerner have had in mind [see ”Patent Prescription,” by Jaffe and Lerner, IEEE Spectrum, December 2004]. Taken together with two significant Supreme Court decisions this year, which reinforced the ”nonobvious” standard and limited the right to obtain an immediate injunction following a patent victory, enactment of the patent reform bill ”would be a major step in the direction” of what Jaffe and Lerner proposed, says Jaffe, of Brandeis University, in Waltham, Mass.

At press time, it's considered a toss-up as to whether patent reform passes this year before the presidential election cycle begins. In any event, Lerner, of Harvard, expresses satisfaction that at least “something's finally happening after a long time of nothing happening.”