Behind the bit-by-bit revelations of Volkswagen's emissions-cheating scandal lies a larger problem: old-line carmakers are increasingly out of their element in a software-driven manufacturing world, aka the Internet of Things.

“The automotive industry’s problem has become one of systems integration, with software one of the main things they’re integrating,” according to Bill Curtis, the executive director of the Consortium for IT Software Quality and an IEEE Fellow. “It’s not the job of a classical mechanical enginer, or even an electrical engineer.” Curtis spoke to Spectrum in late October, before the latest stage in VW’s unfolding scandal.

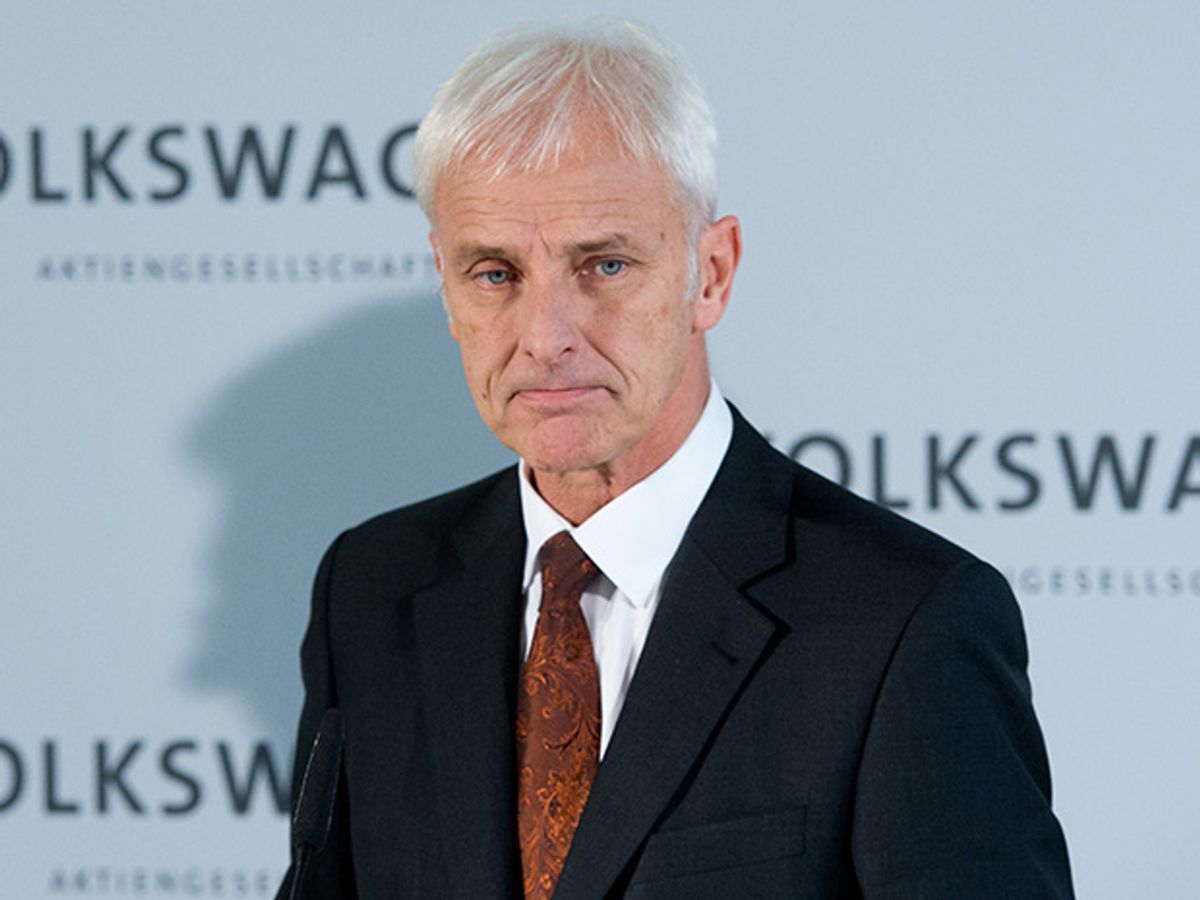

That stage came over the weekend, when Germany’s Handelsblatt reported that CEO Matthias Müller admitted that his company’s software cheat affected not only smaller diesel-powered cars but also the larger, six-cylinder versions offered by the Audi and Porsche divisions. Müller ran Porsche before assuming the top job in late September, replacing Martin Winterkorn, who had departed in disgrace.

The cheat made the cars hew to environmental standards in the lab while flouting them on the road, allowing for nitrous oxide emissions many times higher than what’s allowed in the United States (and significantly higher than the less stringent European requirement). As a result, the U.S. Environmental Protection Agency has announced that it will test more cars on the road than it has done in the past.

It’s easy to blame VW’s culture for frightening underlings into achieving higher management’s goals at all cost, with no questions asked about how they do it. But there is also another, bigger problem with the process by which software is written at all auto companies.

According to Curtis, the modern car is absorbing digital technology far faster than the car companies’ executives can come to understand it.

Of course, the auto companies could simply outsource much of their software development, but that risks letting tech companies eat the car guys’ lunch. This fear is particularly strong in Germany, where reliance on home-grown engineering is deeply ingrained and where suspicion of common platforms controlled by the likes of Google and Apple is rife. That suspicion has a name all its own: Plattform-Kapitalismus, as the Economist noted last week.

At stake is not only adherence to the law but also to standards of quality that affect performance, safety and cybersecurity. “Companies like Boeing have developed really rigorous software testing processes,” Curtis says, as opposed to fixing software after the fact. “They know you cannot test-in quality. I’m not sure the [American] automotives know that yet. You don’t test it in—you design it in.”

German experts, quoted in that Economist article, say that German automakers might derive an advantage from the German method of teaching computer science, which emphasizes precision over speed of development. That would tend to favor the design of very reliable systems—like those that govern safety in a self-driving automobile.

Philip E. Ross is a senior editor at IEEE Spectrum. His interests include transportation, energy storage, AI, and the economic aspects of technology. He has a master's degree in international affairs from Columbia University and another, in journalism, from the University of Michigan.