This is the fourth post in our Startup Spotlight series featuring new robotics companies from around the world. We’re inviting representatives from the companies to describe their technologies and how they see the marketplace. The views expressed here are solely those of the author and do not represent positions of IEEE Spectrum or the IEEE.

Startup Spotlight: syntouch

Founded: June 2008

Location:Los Angeles, Calif.

Focus: Advanced tactile sensing

Founders:Gerald Loeb, Jeremy Fishel, Matt Borzage, Raymond Peck, and Nicholas Wettels

Funding:SBIR grants and product sales

Fun Fact:Swedish scientist Roland Johansson, who helped develop SynTouch’s BioTac sensor, has been studying the human hand for more than 35 years.

As anyone who has ever experienced numb fingers from the cold knows, the human hand is pretty much useless without the ability to feel. At SynTouch, where I’m one of the co-founders, we believe that today’s robotic hands and grippers have been unable to achieve human-like dexterity for the same reason. If a robot can’t feel an object, its ability to manipulate that object will always be limited.

It took more than 50 years from the development of the artificial eye—the video camera—to mature to the widespread application of “machine vision” currently used in autonomous robots, assembly lines, quality control, surveillance, and so many other systems. At SynTouch we have developed an advanced tactile sensor modeled after the human fingertip, and our hope is that this technology and its applications can launch the field of “machine touch.”

When Professor Gerald Loeb, also a SynTouch co-founder, and his research team at the University of Southern California were asked to participate in DARPA’s Revolutionizing Prosthetics project a few years ago, he soon realized that even the best mechatronics couldn’t compensate for the inadequate and fragile technologies then available for tactile sensing.

Together with Roland Johansson at Umea University in Sweden, they dreamed up a biomimetic sensor that would have both the mechanical and the sensing properties of a human fingertip. A prototype developed in Loeb’s lab at USC yielded encouraging results. It was still a crude device, but program managers at the National Institutes of Health and National Science Foundation suggested that Loeb skip traditional academic grants and instead pursue Small Business Innovative Research (SBIR) Grants, to accelerate commercialization. And thus SynTouch was born.

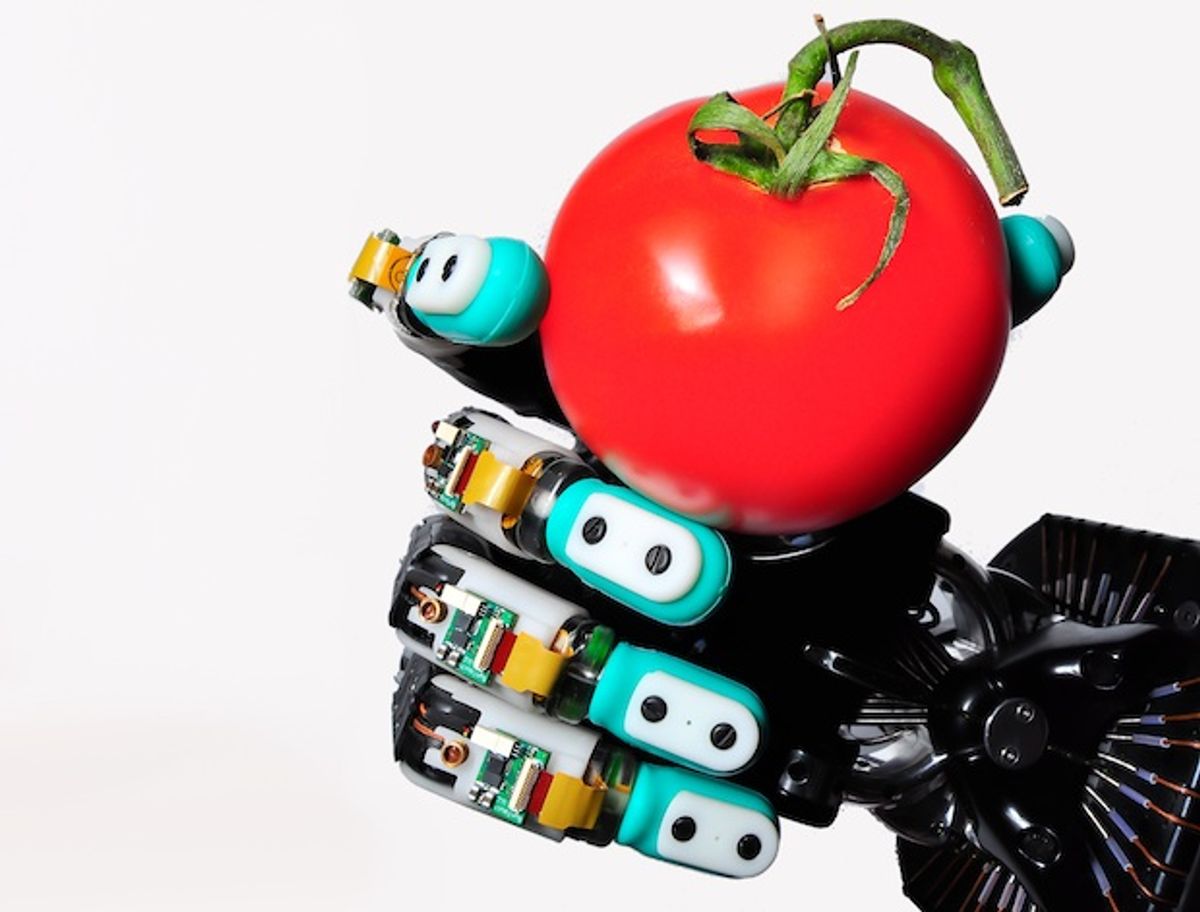

Fast forward to 2013. The company has completed a number of successful SBIR grants and has sold over 100 of its BioTac sensors to a wide range of academic and industrial researchers throughout the world. (The photo above shows a Shadow hand equipped with BioTac fingertips, one of which is pictured below.) The technology itself is based on several biomimetic principles that allow the device to sense point of contact, normal forces, shear forces, vibrations, and thermal gradients just like the human fingertip. With robustness in mind, we have designed the BioTac so that its humanlike skin is inexpensive and easily replaced when it inevitably becomes worn or damaged. And the BioTac has, indeed, provided a simple way to enable users of even simple prosthetic hands to handle delicate objects easily and reliably. Objects like Ritz crackers, for example.

Here’s an overview of how the BioTac works:

But the hardware is just part of the story. Another crucial element was imitating the thought processes that direct the movements and iterative judgments that humans use when exploring a new object. Jeremy Fishel, one of the original USC graduate students and a co-founder, developed an algorithm called Bayesian exploration, which mimics how humans explore and classify objects based on their prior experience. His paper with Loeb in Frontiers of Neurorobotics last year demonstrated 95 percent accuracy in identifying any of 117 common surfaces by texture alone. Manufacturing engineers pounced on it. So now SynTouch is developing specialized robots that slide their sensitive BioTacs over all kinds of products.

In fact, as is often the case with emerging technologies, the killer app will probably be unrelated to the original motivation of prosthetic hands. Everything from clothing to personal electronics to skin care products has to have the right “feel” to customers. Conventional measurements such as profilometry and hardness don’t capture the details of how a given texture will interact with the viscoelastic properties of a human fingertip. The BioTac can capture those details and more. We’re also working on integrating machine touch into robots for manufacturing, surgery, personal-assistance, and military use. And this, we hope, is only the beginning for a technology that one day may literally touch many aspects of people’s lives.

Matt Borzage is head of business development and a co-founder of SynTouch. His background is in biomedical engineering and he worked previously in engineering and sales positions in a medical device company.