Scientists, especially highly successful ones, are often reluctant to write about themselves, to tell their own stories of research and the pursuit of new knowledge. Modesty is only one reason for the furtiveness of the successful scientist. Journalists devote lifetimes to canonizing great scientists, and a chorus of praises from others rather distinctly favors the scientist at the center of the cheering. The scientist who speaks for him- or herself runs the reasonable risk of overlooking the accomplishments of others and inadvertently slighting a less successful worker in the vineyard of science.

Yet in letting others speak, the successful scientist can become a kind of journalistic puppet, an actor in a theater of someone else’s design. Because the rare scientist of great achievement is also a celebrity, he is also tempted to eschew brokers and go-betweens, directly reaching an audience with his or her own words. Today, the TED talk or the “Science Friday” interview is as much a part of the making of great scientists’ reputations as any other documentary aspect of their careers.

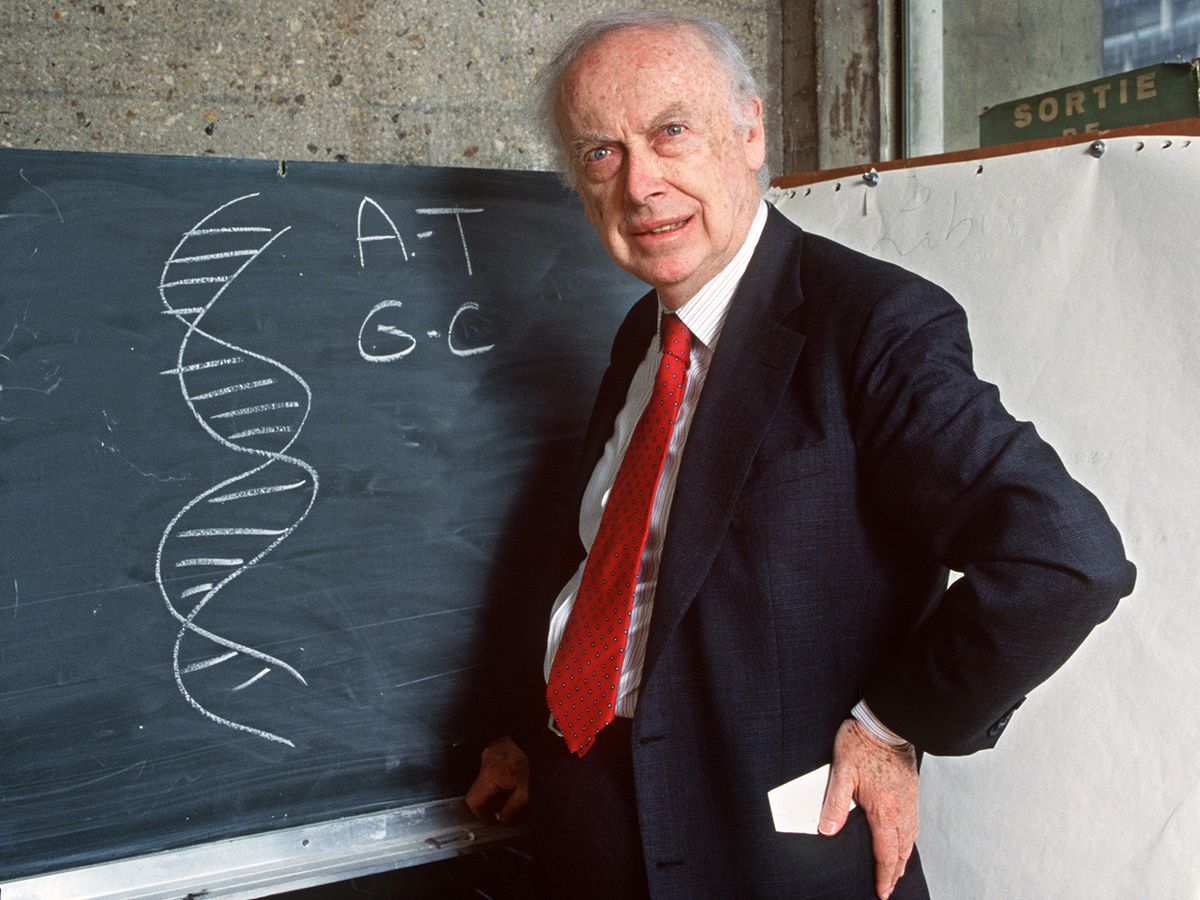

In an earlier era, before the Internet and the democratization of videography, memoir was the preferred method for great scientists of rounding off, and realizing, their reputations in the wider world. Unquestionably, the most successful of these memoirs—recognized as one of the great nonfiction books of the 20th century—is The Double Helix: A Personal Account of the Discovery of the Structure of DNA, by James D. Watson, the great biologist and codiscoverer of the structure of DNA.

Watson’s memoir, which I reread recently as part of my own inquiry into how and why accomplished scientists tell their own stories, is written in a chatty style, punctuated with Watson’s caustic wit and arrogant exuberance. The book recaptures a few years of his early 20s when Watson found his calling in science through a circuitous journey in Europe, where he ended up a friend and colleague of Francis Crick, a loquacious and unsuccessful doctoral student 10 years his senior. The two joined forces at the University of Cambridge’s legendary Cavendish Laboratory.

Together, Watson and Crick clicked. What would Simon be without Garfunkel? Lennon without McCartney? Those musical hookups of legendary stature suggest something of the monumental effects of the partnership between Watson and Crick. Coming from outside of the fields of genetics and chemistry, Watson and Crick gathered together various prominent pieces in the emerging field of molecular biology and quickly created a mathematical model of astonishing clarity and originality. As Watson himself immodestly exults in the pages of The Double Helix, he and Crick had discovered the secret of life and reached one of the greatest scientific milestones of the 20th century.

By the time Watson wrote his memoir, published in 1968, he was already a Nobel Prize winner and a scientific celebrity almost on a par with Einstein or Darwin. So The Double Helix cannot be explained away as an effort to raise the awareness of the intelligent public about the importance of his discovery. Rather, as he explains in his pithy and illuminating (if terribly brief) preface, Watson wishes to combat what he describes as “the general ignorance about how science is ‘done.’ ”

Watson aims to present the pursuit of scientific knowledge, and especially landmark discoveries, as part of the same messy reality as other great human achievements. He pointedly highlights the role of raw ambition in the process, and the importance of human personality generally. An instinctive purveyor of the “great man theory of history,” Watson insists in the preface that “styles of scientific research vary almost as much as human personalities.”

In The Double Helix, there are extra helpings of Watson’s own personality. As the great science journalist Jonathan Weiner has recently demonstrated in his lucid essay on Watson’s memoir in the pages of the Columbia Journalism Review, Watson produced “a great work of literary nonfiction,” yet did so at some cost to the reputations of fellow scientists, some of whom he describes at length (and others whom he altogether ignores).

The merit of Watson’s memoir as historical record, however, isn’t my concern, and not only because I am hardly qualified to sort through the documentary record. That task has been accomplished with great skill by others (including Weiner, a professor at Columbia University’s journalism school). My concern is about the logic and effect of storytelling of a certain sort: by scientists and for consumption of nonscientists (or even for anyone not initiated into a particular scientific discipline, the discipline adopted by the author).

To start with, Watson wants to prove that scientists can spin a good yarn. He also wants to demonstrate that scientists are all too human: consumed by jealousy, rivalry, and petty passions. To inject drama into his tale, he highlights the competitive aspect of science, which he simply calls “the race.” In the case of the structure of DNA, Watson presents the competition as binary: he and Crick versus the legendary American chemist Linus Pauling. In truth, some of Watson’s important collaborators, notably Maurice Wilkins and Rosalind Franklin, were also his rivals, but they failed to realize, as Watson dramatically did, that DNA, far from being a mere scientific curiosity, was an intellectual problem of world historical importance and that whoever cracked this nut would be immortalized. As Watson writes on the opening pages of The Double Helix, “Then DNA was still a mystery, up for grabs, and no one was sure who would get it.”

In the course of his narrative, the mythical field narrows to contain only Pauling and the Watson-Crick team. The latter ultimately won the race, which makes Watson’s tale very much a winner’s story. One unforgettable image, for instance, has Watson and Crick exulting over a silly mistake made by Pauling, which badly slows his research. The relentless attempt by Watson to befriend Pauling’s son Peter, in order to learn more about his father’s research, smacks of the same subversive spirit. However much Watson wishes to make The Double Helix a collective portrait, “a matter of five people,” as he writes, in the end the memoir is his story, and only his.

Does narrative, then, in the hands of a single scientist distort the public’s understanding of science practice by presenting it as a colossal battle of egos as opposed to the conventional view of science that emphasizes groups and teams, cooperation between far-flung people on a vast scale? The Double Helix, for all its virtues, promotes a “distortion field,” which however compelling, creates an immediate need for supplemental sources to give a full picture of the events leading to discovery.

Watson seems only dimly aware of the limits of the solitary scientist speaking for him or herself. Yet he selected to write the foreword to his classic the director of Cavendish, a physicist of great reputation, and a Nobel winner. Lawrence Bragg, born in 1890 and deeply imbued with the British sense of casual humility and fair play, would never have written a chatty, self-congratulatory memoir of the sort Watson delivered. Nonetheless, he recognized how, in the wake of World War II and the enormous contributions of scientists to the war and its aftermath, the reality and image of the scientist would never be the same. To Bragg, The Double Helix isn’t history, nor simply an entertaining tale, but rather “an autobiographical contribution to the history which will some day be written.”

Indeed. Of all the concessions Watson made to great storytelling, historical understanding is the greatest. As Weiner acidly recalls in his recent essay, Watson overlooks completely the role of the Rockefeller Foundation research team that actually identified DNA as the crucial actor in the drama of human genetics. And then there is the wider historical awareness of which Watson appears utterly ignorant. He and Crick published their pathbreaking paper in 1953, merely eight years after the first Trinity atomic explosion. The Cold War between the United States and the Soviet Union kept government money pouring into scientific activities, lubricating the private dramas of narcissistic heroes like Watson. So when he crows at the end of his rattling yarn that he and Crick had staged “perhaps the most famous event in biology since Darwin’s book,” he was only acting as one of the burgeoning members of a scientific priesthood.

In a world ceaselessly remade by science and technology, where the lines between disciplines blur again and then again, the sort of boundary jumping achieved by Watson and Crick seems to both presage and validate new pathways to discovery. Watson manages in The Double Helix to canonize the scientific priesthood and himself, while at the same time highlighting the similarity between the practice of science and engineering, where the pursuit of goals and solutions matter as much as the joys of pure discovery.

A version of this article appeared in the blog As We Now Think, sponsored by the Consortium for Science, Policy & Outcomes at Arizona State University.

About the Author

G. Pascal Zachary is a professor of practice at the Consortium for Science, Policy & Outcomes at Arizona State University. He is the author of Showstopper!: The Breakneck Pace to Create Windows NT and the Next Generation at Microsoft (The Free Press, 1994), on the making of a Microsoft Windows program, and Endless Frontier: Vannevar Bush, Engineer of the American Century (The Free Press, 1997), which received IEEE’s first literary award. Zachary reported on Silicon Valley for The Wall Street Journal in the 1990s; for The New York Times, he launched the Ping column on innovation in 2007. The Scientific Estate is made possible through the support of Arizona State University and IEEE Spectrum.