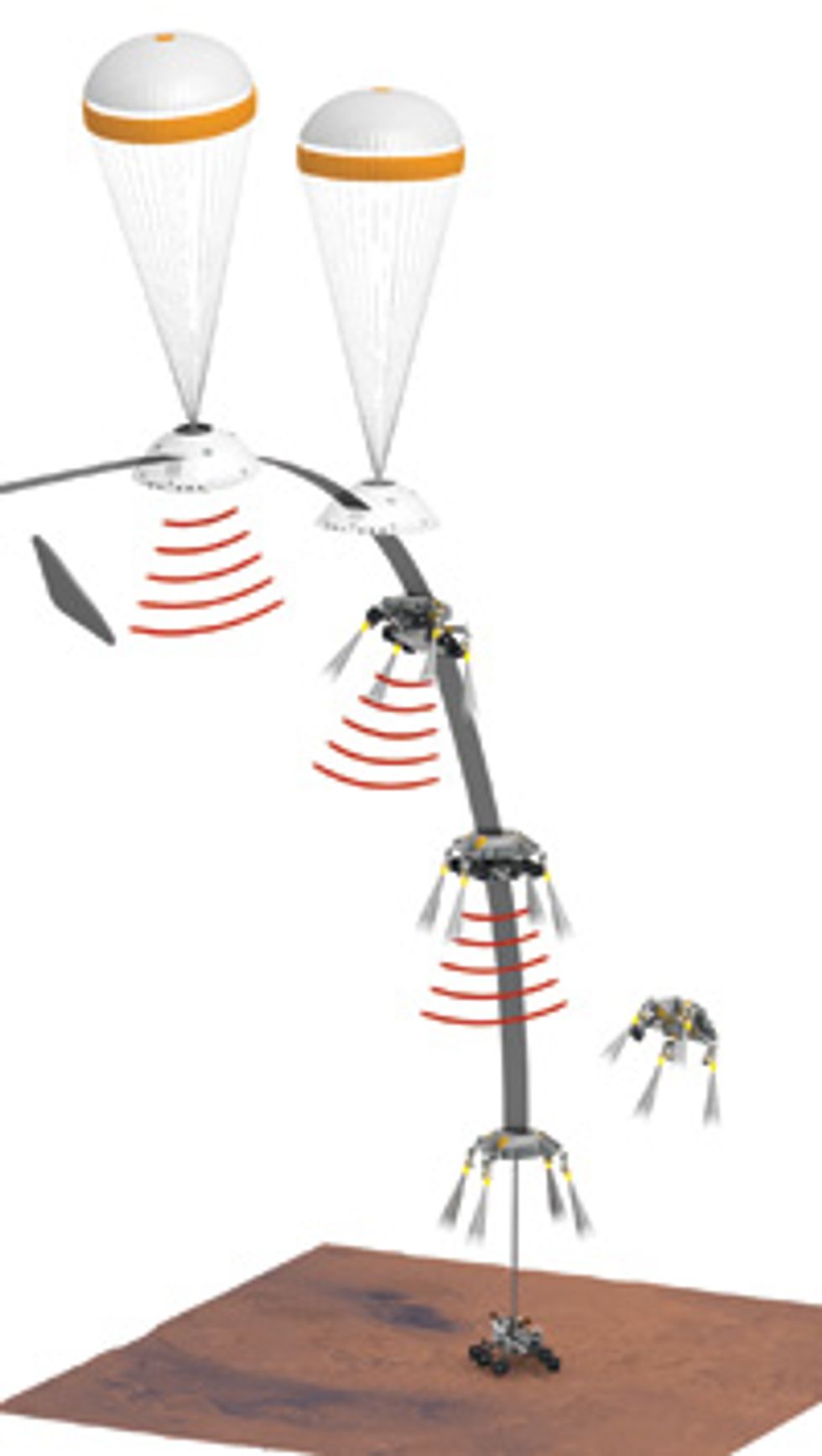

On 6 August, NASA’s robotic rover Curiosity is scheduled to reach the end of its eight-month journey to Mars and begin its high-stakes descent down to the surface of the Red Planet. In 7 nail-biting minutes, the spacecraft must transform a 5.9-kilometer-per-second approach into a soft landing near the foot of the Martian equatorial mountain Aeolis Mons. And with a 14-minute communications lag between Mars and Earth, Curiosity’s computer will have to perform the feat all on its own. [For minute-by-minute details on the landing, click on the illustration at right.]

Two sensor systems, both stored in the spacecraft’s descent stage, will prove crucial to safely landing the hefty, 900-kilogram robotic rover. One of those is the spacecraft’s Descent Inertial Measurement Unit (DIMU), a Honeywell-made device containing three gyros and three accelerometers. For more than half the landing, until about 2 minutes from touchdown, Curiosity will be flying blind, relying entirely on DIMU data to estimate the spacecraft’s position, orientation, and speed, and by extension, its likely altitude.

NASA Jet Propulsion Laboratory’s Steven Lee, who is the guidance, navigation, and control systems manager for the mission, likens this stage of the descent to riding in the passenger seat of a car with your eyes closed. You can use your inner ear and sense of touch to approximate the location of the car, assuming you know its starting point. The spacecraft essentially uses its “vestibular system to get in the vicinity,” Lee says.

But to get the precision needed for the last moments of landing, the spacecraft’s descent stage will need to open its eyes. About 8 km above the planet’s surface, the robot’s heat shield will drop away, revealing six independent pulsed-Doppler radar antennas. Distance readings from this JPL-designed, long-range radar system will be used to signal when the parachute should be detached, when retro-rockets should fire, and when the rover should be lowered down from the descent stage. If all goes well, Curiosity will make the most precise landing yet attempted on the Red Planet, and 14 or so minutes later, a host of engineers will toast the achievement.

This article was updated on 14 August 2012.